Giiwas/Crater Lake

by Stefan Livo, 11/16/2018.

Summary

A tribal tradition shared by the Klamath Tribes (Klamath, Modoc, Yahooskin) remembers the devastating battle between mythical characters that blew up an entire mountain and turned their land into a sea of fire. Very likely, the stories describe how their ancestors witnessed the collapse of Mount Mazama many millennia ago and how the once mighty volcano was transformed into the famous place called Giiwas by the tribes and Crater Lake by the Euroamerican newcomers. Predating geological studies about the crater, these landmark stories testify to the Klamath Tribes’ ancient presence in the area, their intimate ties to the land, and the stupendous storage capacity of their oral traditions. However, with the arrival of the first white settlers the tribes’ knowledge of and claims to the land have been challenged.

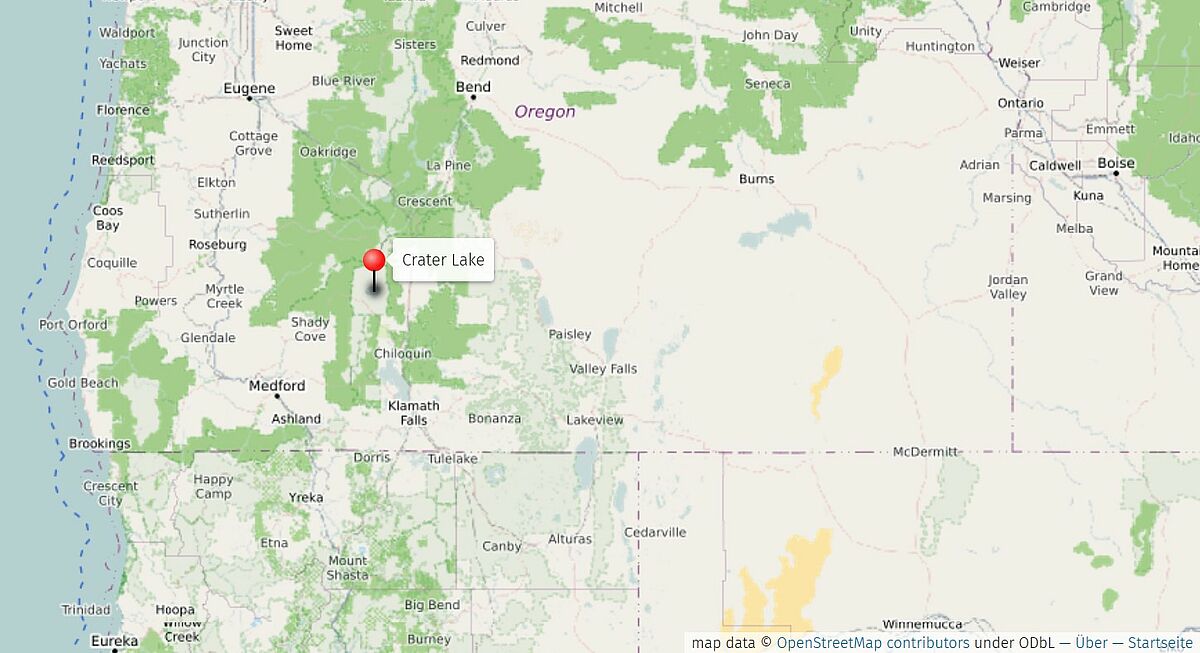

Giiwas/Crater Lake is the site of a cataclysmic event that occurred some 7,700 years ago in Southern Oregon. It is also a place that has been sacred to the Klamath Tribes (Klamath, Modoc, Yahooskin) and their ancestors (the Ma’Klaks) for millennia. The term ‘Crater Lake’ may refer to both: the volcanic crater and the lake located inside. In the Klamath/Modoc language the crater, located at an altitude of 7,000 to 8,000 feet (2,100 to 2,400 m), is called Tum-sum-ne (“the big mountain with top cut off”) while the lake itself is called Giiwas or Gii-was (Alatorre in Juillerat, 11). Crater Lake features prominently in Klamath and Modoc oral tradition, which records the origin, transformation, and spiritual significance of the site.

Oral traditions about the origins of Crater Lake variously describe a violent battle between two spirits or chiefs in ancient times. One of the two spirits or chiefs, identified as Lao, lives inside Moyaina – the mountain which the settlers named Mount Mazama (so named later after the mountaineering group ‘The Mazamas’) only after they had reconstructed the cataclysmic event that had generated Crater Lake. According to the version now best known (Colvig/Clark), Lao gets angry when he is rejected by the beautiful maiden Loha, the daughter of a human chief. The other spirit chief is commonly represented as Skell and has his lodge at Mount Shasta; in many other traditions it is at Yamsay Mountain not too far away. The two adversaries stand on their mountain tops and hurl fire balls at each other until Lao’s mountain collapses, swallowing him in a fiery pit. This version of this story was provided by Judge William M. Colvig, who was a soldier at Fort Klamath and reportedly first heard the story from the old Klamath Chief Lalek in 1865. But in the only extant manuscript, Colvig writes that he lost the original transcript of the story on his travels in a river nearby. He claims that he wrote down several versions of it afterwards (in 1892, 1912, and in 1921). In his last version, he describes the fiery battle and how it affected the landscape and the local tribes:

“The mountains crumbled beneath the tread of the giants who from their summits hurled the Curse of Fire over all the land. Fire spewed from the mouth of Kequila Tyee [Lao], and like an ocean of flame devoured the forests and swept on till it reached the homes of the people. Red hot rocks, as large as the hills, went hurling athwart the midnight skies. Burning ashes fell like rain. The people rushed into the waters of the lake in order to escape the fiery curse. Mothers stood holding their babes in their arms and praying that the mighty war of the gods might end.” (Colvig, 1921)

William Colvig was not a trained folklorist or ethnographer. He recorded the story based on his memory of his conversation with Klamath Chief Lalek. According to Colvig (1921), both of them spoke the Chinook Jargon and Lalek spoke broken English. Other stories were collected by the Swiss-American linguist Samuel A. Gatschet and the amateur folklorist Jeremiah Curtin, who had reached some proficiency in the Klamath/Modoc language and recorded a significant corpus of texts relating to Giiwas/Crater Lake.

Gatschet visited the Klamath in the fall of 1877 and published his research in The Klamath Indians of Southwestern Oregon (1890) in two volumes. The book provides interlinear (word by word) translations of Klamath stories such as “The Mythic Tale of Old Marten”, which Gatschet obtained from Minnie Froben – the daughter of a Klamath woman and a French settler. The story introduces the transformer and culture hero Gmukamps in the shape of Old Marten and his younger brother Weasel.[1] At one point, Old Marten encounters a woman who is being pursued by the Thunders. Old Marten decides to go to the Thunders’ lodge and kill them:

“Old Marten set fire on the lodge, and standing on its top he waited for the Thunders to rush out. He hearkened standing outside; at last, when the fire blazed strongly, the Thunders awoke. They stabbed each other with the long blades, ‘Marten’s younger brother is killing you!’ But they stabbed only each other. Then all perished by blazing up; one heart exploded while flying off.” (Gatschet I, 114)

The story with all its thunders and fire has been interpreted in terms of some cataclysmic geological or meteorological event. Even though this version, collected by Gatschet, does not point to a specific location, Gatschet elsewhere in his book connects the event to Giiwas/Crater Lake. Similar to the Lalek/Colvig story, the great transformer Gmukamps helps a Klamath woman by engaging in a battle of cataclysmic scale. The existence of other similar stories among the Modoc suggest that these texts are part of a millennia old cycle of oral traditions that record – and aesthetically ‘work through’ – the collapse of Mount Mazama and the creation of Crater Lake.

Another well-known set of stories deals with the creation of Wizard Island, a volcanic cinder cone in the waters of Crater Lake. According to Klamath and Modoc oral tradition, the island is the result of another violent battle between the same mythical figures. Captain O.C. Applegate, an agent at the Klamath Indian Reservation around 1900, recorded “The Klamath Legend of La-o” describing a between Skell (i.e. Gmukamps) and Lao. First, Lao and his followers (monsters and giant crawfish) from Crater Lake obtain Skell’s heart and use it in a ball game on a field near Crater Lake. Skell’s followers attend the event and recapture their master’s heart during the ball game, bringing him back to life. Skell overpowers Lao and feeds the pieces of Lao’s body to the creatures in Crater Lake, making them believe that these are the remains of Skell. Only when Skell throws Lao’s head into Crater Lake, the creatures recognize their master’s remains, leaving behind the head in horror. Lao’s head was subsequently transformed into Wizard Island.

Gatschet and Curtin attest to similar stories in their studies of Klamath and Modoc oral traditions. Gatschet (I, xcviii-xcix) merely mentions that Wizard Island represents the remains of a giant, who was killed in a battle with the aforementioned Marten (Skell). Curtin’s Modoc story “Mink and Weasel” connects the story of how Mink (i.e. Gatschet’s Old Marten) and Weasel defeat the Thunders with the creation of Wizard Island. After their victory over the Thunders, the two brothers meet an old man, who introduces himself as an angry relative of the Thunders. The monstrous old man challenges Mink and threatens to feed him to his children living in Crater Lake. Yet just as in Applegate’s story, Mink overpowers his opponent and feeds the old man’s body parts to his own children:

“Then he cut the body up and threw it piece by piece into the lake. As he threw the pieces, he called out: ‘Here if Tskel’s [Mink’s] shoulder! Here are Tskel’s ribs! Here are his legs! Here are his arms!’ As fast as he threw the pieces, the old man’s children caught and ate them. At last he threw the head. It was an awful-looking thing, enough to scare any one.” (Curtin, 296)

With this act, the transformer and creator Marten/Mink has defeated both the Thunders and the evil giant.

As this polymorphous oral corpus suggests, these tribes possess a collective memory of Crater Lake as a site of violent geological events. The age of those events was only ascertained by modern geology which performed its own, and rather different, ‘reading’ of the site (Williams, Harris). Other stories of the Gmukamps corpus contain descriptions of an ocean of pitch that covers the world and similar stories that seem to remember volcanic eruptions (see Curtin and Gatschet). The landmark stories thus show the region as a thoroughly volcanic landscape inscribed with cultural memories of past disasters. For instance, the ball game with Skell’s head is connected to a specific site at the northern slope of Crater Lake, still known as the ‘ball court’ or the ‘ballfield’ (Barker, 73; Deur, 62pp.). The stories can be read alongside the results of archaeological research confirming that Indigenous people have lived in the area affected by the eruption at Giiwas more than seven millennia ago.[2]

A Transculturally Constructed Landmark

With the rediscovery of Crater Lake by Euroamericans in the 1850s, the interest in stories about the landmark grew rapidly. Local citizens traveled to the site to admire the grandeur of the crater and published romanticized accounts of their journeys in newspapers. It did not take long until they started looking for names for the ancient landmark. Suggestions ranged from Chauncy Nye’s “Blue Lake” in 1862 to Captain F.B. Spragues’s “Lake Majesty” in 1865, until the lake was finally named “Crater Lake” by Jim Sutton in 1869 (NPS, “History”). Yet the (re)naming of Giiwas was only the beginning of a greater transformation. In 1870, a young man named William Gladstone Steel learned about this unique landmark. When he first saw the lake with his own eyes in 1885, he was so moved that he made it his goal to turn the site into a national park. The sacredness of Giiwas was thereby confirmed but its use as an Indigenous sacred site became compromised by its significance as a touristic site in non-Indian culture.

Steel and his supporters knew that the local tribes had ancient stories that tied them to their land and to Giiwas, but these ties could pose a problem to Steel’s attempt of claiming the crater as a national park. Steel referred to stories he heard from Klamath tribal members such as Chief Allen David’s “Legend of the Llaos”, first published in his The Mountains of Oregon (1890). In the same volume Steel states:

“There is probably no point of interest in America that so completely overcomes the ordinary Indian with fear as Crater Lake. From time immemorial, no power has been strong enough to induce him to approach within sight of it. For a paltry sum he will engage to guide you thither, but, before you reach the mountain top, will leave you to proceed alone.” (Steel 1890, 15)

Interestingly, this misinterpretation of the Indians’ cultural attitude to Crater Lake (regarding it as a special site that is off bounds for profane visitors) was popularized around the time that Steel’s vision of turning the site into a national park took shape. Just a few years earlier other visitors had attested to the common tribal custom of visiting mountains like Crater Lake to mourn the deceased or talk to the spirits, and they would leave behind “high piles of rock to show how faithfully they have performed their vows” (New York Times 1873, 3). The fact that members of the local tribes have visited Crater Lake for spiritual guidance has been confirmed by anthropological studies (e.g. Deur, Spier, Ray). In the context of their spiritual quests, tribal members have built rock cairns and prayer seats, and they continue to do so to this very day (Haynal). Yet Steel boldly claimed that “[p]revious to 1886 no modern Indian ever looked upon Crater Lake” (1907, 41) and rejected tribal traditions as “superstition” (1890, 12). This line of argument conveniently suggested that it would pose no ethical dilemma to turn Crater Lake into a National Park since the Klamath Tribes did not visit or ‘use’ the lake anyway, while also denying that the Klamath Tribes had an intimate knowledge of the landmark.

Sensing the force of volcanic activity, Steel himself pictured the story of Crater Lake in accordance with the romantic trope of the grandeur of the American West:

“What an immense affair it must have been, ages upon ages ago, when, long before the hot breath of a volcano soiled its hoary head, standing as a proud monarch, with its feet upon earth and its head in the heavens, it towered far, far above the mountain ranges, aye, looked far down upon the snowy peaks of Hood and Shasta, and snuffed the air beyond the reach of Everest.” (Steel 1890, 32)

Depictions like these might have helped to attract visitors to the lake, but they also showed that most of the early reconstructions of the former mountain were mere speculations. In 1883 Everett Hayden and Joseph S. Diller were the first US Geological Survey geologists to visit Giiwas. Three years later geologist Clarence Dutton led a small team to conduct soundings of the lake. The first extensive geological survey was published by Diller in 1897. Diller’s study matter-of-factly describes how Mount Mazama collapsed during a violent eruption some millennia ago. Later publications such as Howell Williams’ Crater Lake: The Story of Its Origin (1963; 1941 as popular short version) reconstruct the eruption of Mount Mazama in a narrative full of colorful imagery and accompanied by the grand paintings of Paul Rockwood, which Rockwood in turn painted based on Williams’ instructions. In the following decades numerous scientists conducted research on the volcanic eruptions, the resulting rock formations, and the impact on local people, fauna, and flora. Next to the Klamath stories about Crater Lake a whole scientific (geological, archaeological) archive of landmark knowledge took shape.

Contested Space and Sacred Site

Their long-term presence in Southern Oregon notwithstanding, the tribes’ ancient claims to their land and Crater Lake were contested since the first Euroamericans visited the lake in the 1850s. They benefitted from the settlers’ fascination with the sublimity of the landscape at Crater Lake which caused the US government to turn the area into a national park in 1902. But the fact that Crater Lake became a tourist hotspot aggravated its use as a sacred site. Giiwas, now open to the public, became a busy place in the twentieth century. Increasing numbers of tourists scaled the slopes of the crater to behold the blue waters of the lake. More recently, boat tours on the lake were made available and cars began to crowd the rim drive. Yet despite these negative effects on the sacredness of the place, the establishment of a national park also protected the area from real estate development and industry. In spite of the national park’s colonial beginnings, the National Park Service (NPS) has, more recently, promoted a respectful treatment of Crater Lake, as a site that can be enjoyed and held sacred by different groups of people (NPS, “History”).

This transcultural project of combining Indigenous and Western perspectives and knowledges of the land is an important aspect of our research project. The case of Crater Lake illustrates the benefits of shared efforts to protect unique places, but it also shows the conflicts that can arise. In In the Footprints of Gmukamps (2008) anthropologist Douglas Deur studies the relationship of local tribes (e.g. Klamath, Modoc) with national parks like Crater Lake or the Lava Beds. In interviews tribal members reveal their strong ties with the sacred places of their land and how recent history has threatened these ties. In 1864, shortly after the rediscovery of Crater Lake, the Klamath, Modoc, and Yahooskin Tribes were forced onto a shared reservation. When the Klamath were legally terminated as a tribe in 1954 (under the pretense of being assimilated into American society), they lost their complete land base. This loss made it difficult for the tribes to preserve their traditional knowledge of the land since the land “provides them with a sense of connection both to ancestors of the distant, pre-contact past, as well as to individuals of the last century” (Deur 2008, 34).

Despite termination, assimilation policies, and governmental appropriation of Indigenous land, the Klamath Tribes and their knowledge about Crater Lake survived. Their efforts were rewarded when their tribal status was restored in 1986. Annual culture camps and other events at Crater Lake continue to restore the tribes’ bond with Giiwas and preserve their knowledge of the landmark. Indigenous knowledge about Crater Lake was also preserved by non-Indian writers like Gatschet, Curtin, and Barker who recognized the unique value of these landmark stories. Publications such as Stanton C. Lapham’s The Enchanted Lake (1931), Ella E. Clark’s Indian Legends of the Pacific Northwest (1953) and Stephen Harris’ Fire Mountains of the West (1988) emphasize the connection between Indigenous knowledge and geological studies and depict Crater Lake as a contested and transculturally shared sacred place that instills awe in visitors of many different cultural backgrounds – while remaining sacred only to Indigenous groups whose knowledge of this place extends to the depths of time.

While Giiwas itself is today protected from industrial encroachments, the Klamath and Modoc have currently joined non-Indian activists in resisting the building of a long-distance pipeline for highly combustible liquid gas through the volcanic Crater Lake region. They know what can happen if Gmukamps gets angry again ….

NOTES

[1] Gmukamps is a trickster-transformer figure and assumes various characters and names in the different stories (e.g. Marten, Mink, Skell, Chief of the Above World). Additionally, the people writing down or transcribing the original Klamath/Modoc language used different spellings for the same name. This also applies to the other characters in the stories. To avoid confusion, this article will stick to one way of spelling and indicate overlaps among figures only where necessary.

[2] Archaeological finds from the area date the Indigenous presence back to at least 9,000 and, more recently, as much as 15,700 years before present (e.g. Cressman, Aikens et al.). These findings (at Oregon’s Paisley Caves) challenge, once again, the Clovis First consensus which rejects such an early human presence in North America.

WORKS CITED

Aikens, C. Melvin, Thomas J. Connolly, and Dennis L. Jenkins. Oregon Archaeology. Portland: Oregon State University Press, 2011.

Applegate, Oliver C. “The Klamath Legend of La-o.” Steel Points 1, 2 (1907) 75-76.

Barker, M. A. R. Klamath Texts. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1963.

Clark, Ella E. Indian Legends of the Pacific Northwest. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1953.

Colvig, William M. “The Legend of Crater Lake.” Manuscript from a Private Collection of Tim Colvig, Oakland, Dated 1921. We express our gratitude to Tim Colvig for allowing us to use this manuscript.

“Crater Lake. The Most Wonderful Body of Water in the World.” New York Time July 27, 1873, 3.

Cressman, Luther S. The Sandal and the Cave. 1981. 2nd ed. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 2005.

---. Prehistory of the Far West. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press,1977.

Curtin, Jeremiah. Myths of the Modocs. Boston: Little, Brown, and Co., 1912.

Deur, Douglas. In the Footprints of Gmukamps. A Traditional Use Study of Crater Lake National Park and Lava Beds National Monument. National Park Service. Pacific West Region, 2008.

Diller, Joseph S. "Crater Lake, Oregon.“ The National Geographic Magazine 3, 2 (1897) 33-48.

Gatschet, Albert Samuel. The Klamath Indians of Southwestern Oregon. 2 Vols. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1890.

Harris, Stephen L. Fire Mountains of the West. The Cascade and Mono Lake Volcanoes. Missoula: Mountain Press Publishing Company, 1988.

Haynal, Patrick M. “The Influence of Sacred Rock Cairns and Prayer Seats on Modern Klamath and Modoc Religion and World View.” Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology 22, 2 (2000). 170-185.

Juillerat, Lee. “Legendary Crater Lake. Tales of the Lakes’ Creation and Monsters that Dwell Within.” Klamath Life July/August (2015), 10-12.

Lapham, Stanton C. The Enchanted Lake. Mount Mazama and Crater Lake in Story, History, and Legend. Portland, OR: J.K. Gill Co., 1931.

National Park Service. “Crater Lake. History”. N.p., 2001. <https://www.nps.gov/crla/planyourvisit/upload/History-508.pdf> last accessed November 15, 2018.

Ray, Verne, F. Primitive Pragmatists: The Modoc Indians of Northern California. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1963.

Spier, Leslie. Klamath Ethnography. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1930.

Steel, William Gladstone. The Mountains of Oregon. Portland: David Steel, 1890. 12-33.

---. “Crater Lake.” Steel Points 1, 2 (1907).

Stern, Theodore. The Klamath Tribe. A People and their Reservation. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1965.

Williams, Howell. Crater Lake. The Story of its Origin. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1941/1963.

ILLUSTRATIONS

Figure 1: Rockwood, Paul. “Mount Mazama Erupting.” 1940. Painting. Crater Lake National Park Museum and Archives Collections. Crater Lake.

Figure 2: Livo, Stefan. “Wizard Island.” 2016. JPEG.

Figure 3: Rockwood, Paul. “Mount Mazama After the Cataclysmic Eruption” 1940. Painting. Crater Lake National Park Museum and Archives Collections. Crater Lake.