Tanmahawis/The Bridge of the Gods

by Stefan Krause, 11/06/2017.

Summary

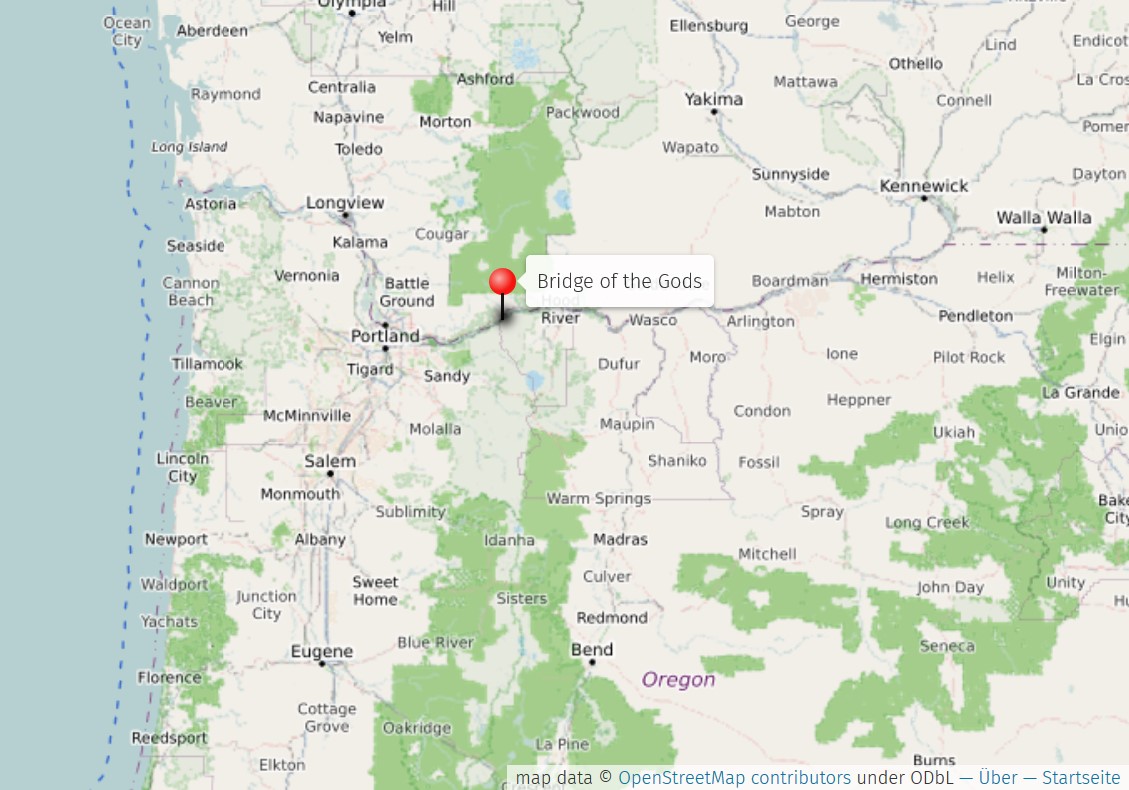

Long before the Columbia River was crossed by man-made bridges a natural bridge had traversed the waters. Local tribes like the Klickitat, Wasco, Wishram, Yakama, and Colville remember how a rumbling ‘battle’ between mountains created a rock structure that dammed up the river and allowed the people to cross – Tanmahawis/The Bridge of the Gods. Some three hundred years later, in the eighteenth century, the bridge collapsed and left behind the roaring Cascade Rapids. But what did it look like? What does this ‘landmark story’ tell us about how the Bridge of the Gods was created and destroyed?

The Bridge of the Gods in Indigenous Traditions

The Klickitat, Wasco, Wishram, and other tribes had lived along the Columbia River long before the ‘Bridge of the Gods’ collapsed. The landmark received its English name with reference to their traditions, which describe how the Great Spirit created the structure and testify to the spiritual importance of the site. Some of the oral traditions have been recorded by pioneers, folklorists, and anthropologists. Despite a few differences, these texts share general elements. The stories usually involve the battle between the neighboring mountains (Mt. Hood, Mt. St. Helens, and Mt. Adams) through which the bridge is eventually destroyed. Ella E. Clark’s essay “The Bridge of the Gods in Fact and Fancy” gives an overview of other Native accounts (e.g. by the Yakama and the Colville). In contrast to geological studies, which focus on the events that created the bridge, many recorded oral traditions focus on the creation and the collapse.

According to historian William D. Lyman, geologist George Gibbs was probably the first to record an indigenous oral tradition about the Bridge of the Gods. Gibbs obtained the text when he was talking to members of local tribes during his geological work for the Pacific Railroad in 1853. Lyman cites Gibbs in his essay “Indian Myths of the Northwest” (1915).

"The Indians tell a characteristic tale of Mt. Hood and Mt. St. Helens to the effect that they were man and wife; that they finally quarreled and threw fire at one another, and that St. Helens was victor; since when Mt. Hood has been afraid, while St. Helens, having a stout heart, still burned. In some versions this story is connected with the slide which formed the Cascades of the Columbia." (386)

One of the most famous versions was recorded by Clarence O. Bunnell, who heard the story when he was a little boy. His book consists of a cycle of texts that illustrate how culture hero Coyote transformed the land and how a great inland sea covered the land east of the Cascade Range. When “Squaw Mountain” moves to a valley between the mountains Yi-East (Mt. Hood) and Pa-toe (Mt. Adams), Yi-East and Pa-toe engage in an angry fight over “Squaw Mountain.”

“During their fight the mountains had shaken the Earth so hard that a hole had been torn through the base of the mountain range between Pa-toe and Yi-East. Through this the waters of the inland sea had raced in their mad hurry to escape the wrath of the fighting mountains, tearing out more and more of the earth and rocks until a great tunnel was formed under the mountain range, leaving a wonderful natural bridge beneath which flowed a peaceful, though worried, river.” (17/18)

“Squaw Mountain” goes into hiding, but when she returns to her beloved Yi-East, the fight continues and the bridge including its guardian – the old and faithful woman Loo-wit – fall. Eventually, Loo-wit is turned into a beautiful mountain (Mt. Saint Helens) and Coyote clears the river channel of the bridge’s debris.

Rancher, frontiersman, and amateur historian Lucullus V. McWhorter recorded a quite different version from Wasco informant An-a-whoa. In the text, Thunderbird (Noh-we-nah-kláh) erects five mountains (“five laws”) to keep the people from traveling west towards the sunset. Coyote challenges Thunderbird and a thunderous battle ensues until Coyote finally wins.

“Noh-we-nah-kláh, shrank deeper in the water; scared! Coyote, above him and invisible, now brought a greater noise than ever; a crash like the bursting of this world. The five laws, the five mountains, crumbled and fell. The fragments, floating down the nChe-wana [Columbia River], created many islands along its course. The giant body of Noh-we-nah-kláh, formed the great Bridge across the wana at the Cascades. This Bridge was of the first mountain, and was mostly stone. It stood for many hundreds of snows; no one knows how long, and then it fell.” (6)

Reconstructing the Story of a Landmark

By the time of the arrival of the first white explorers and settlers, the Bridge of the Gods was no more. On the 30th and 31st October 1805, Lewis and Clark first passed the site and found tree stumps projecting into the river. Instead of a land bridge, they encountered rocks and wild rapids (Cascade Rapids). On their return trip eastward, Lewis speculated that “the narrow pass at the rapids has been obstructed by the rocks which have fallen from the hills into that channel within the last 20 years” (The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, April 14, 1806). In the following years, travelers, settlers, and missionaries described the site. In “The Evolving Landscape of the Columbia River Gorge – Lewis and Clark and Cataclysms on the Columbia,” Jim E. O’Connor provides a historical overview of the reports made by European-American travelers and geologists. All these visitors were confronted with the same question: what event had caused such a transformation of the landscape? Recent geological publications track the creation of the Bridge of the Gods back to a landslide in the first half of the fifteenth century (e.g. Randall, Reynolds et al.). The ‘bridge’ traversed the Columbia River for some 300 years until it probably collapsed in the second half of the eighteenth century. According to Ella E. Clark, Old Henry of a local tribe dated the collapse to a time around 1750-1760, based on oral accounts (38).

Reconstructions of the former landmark vary and often they remain quite vague. Geological reports only give a few details on what the bridge might have looked like and how it affected the life of local populations. Geologist Patrick Pringle plainly pictures the bridge as a “pile of rocky landslide debris that allowed people to walk from one side of the river to the other” (2). The Klickitat and other tribes remember several distinct aspects of the bridge through oral traditions. For example, their stories illustrate that the former landmark resembled a tunnel or underground passage more than a bridge. Bunnell describes how Koyoda (Coyote) and a group of men journey through the dark tunnel under the bridge, mentioning that “from the time of passing into the tunnel there was a strong current of fresh air blowing against their faces” and that “[m]ost Indians tell of the darkness in this tunnel” (25). Travelers in the nineteenth century, like Gustavus Hines, also confirmed that the local tribes “have a tradition that, a long time ago, the mountain was joined together over the river, and that the river performed a subterraneous passage for some distance” (155). McWhorter’s notes also reveal reports of the Klickitat, according to which only the oarsmen would stay in the canoe when traveling through the dark tunnel (8). The oarsmen would bid the others goodbye for there was a prophecy that predicted the collapse of the rock structure. All this information illustrates the tribes’ deep understanding of their land and its past, and bears witness to the long history of their habitation of the Columbia River Valley.

However, most of the popular portraits of the bridge seem to neglect details from the traditions of the Klickitat and other tribes. Murals like the one depicted above, and drawings like Jimmie James’ The Legendary “Bridge of the Gods” show the bridge as an enormous rock arch, which seems to be inspired by landmarks such as the Natural Bridges National Monument in Utah or Hudson River School landscape paintings such Thomas Cole’s Evening in Arcady (1843). These visual reconstructions of the natural bridge praise the sublimity of the landscape of the American (North)-West while neglecting the indigenous origin of ‘Bridge of the Gods’ as landmark story and spiritual place in the traditional land of the Klickitat, Wasco, Wishram, and others. The enormity of the gaping arches in these portrayals also poses the general question as to how the bridge could have dammed up the river to form a lake/inland sea. Obviously, artists may have been inspired by other representations of natural bridges, which resulted in visual mistranslations.

The story of the Bridge of the Gods also inspired pieces of fiction such as Frederic H. Balch’s Bridge of the Gods: A Romance of Indian Oregon (1890) and poems such as Samuel A. Clarke’s “Legend of the Cascades” (1874). While Balch incorporates Native oral traditions into his romanticized text in, Clarke puts various indigenous traditions in verse. Both approaches altered the indigenous texts, but also made them more accessible to the general readership. The Bridge of the Gods then has become a landmark story transculturally negotiated between indigenous memory, geological research, and American Old West romanticism. It shows how America’s pre-contact past is best reconstructed in a transcultural and polyvocal approach that combines Western sciences and indigenous knowledge.

WORKS CITED

Balch, Frederic H. Balch’s Bridge of the Gods: A Romance of Indian Oregon. Chicago: A.C. McClurg and Company, 1890.

Bunnell, Clarence Orvel. Legends of the Klickitats. A Klickitat Version of the Story of the Bridge of the Gods. Portland, OR: Metropolitan Press, 1933.

Clark, Ella E. “The Bridge of the Gods in Fact and Fancy.” Oregon Historical Quarterly 53.1 (1952), 29-38.

Clarke, Samuel A. “Legend of the Cascades.” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine 48, 285 (1874), 313-319.

Hines, Gustavus. A Voyage round the World with a History of the Oregon Mission. Buffalo: George H. Derby and Co., 1850.

Lyman, William D. “Indian Myths of the Northwest.” Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society. Vol. XXV (1915) 375-395.

McWhorter, Lucullus V. Papers, 1848-1945. Cage 55. Manuscripts, Archives, and Special Collections, Washington State University Libraries, Pullman, WA. Box 44, Folder 429. Finished Stories. 1911-1924. "Bridge of the Gods." Wasco. Narrated by An-a- whoa*: "black-bear," Sept. 1914. Notes, McW.

O'Connor, Jim E. “The Evolving Landscape of the Columbia River Gorge-Lewis and Clark and Cataclysms on the Columbia.” Oregon Historical Quarterly 105.3 (2004): 390- 421.

Pringle, Patrick T. "The Bonneville Slide". Columbia Gorge Interpretive Center Museum Explorations, Fall-Winter (2009): 2-3.

Reynolds, Nathaniel D. et al. “Age of the Bonneville Landslide and the Drowned Forest of the Columbia River, Washington, USA—From Wiggle-Match Radiocarbon Dating and Tree-Ring Analyses.” 10th Washington Hydrogeology Symposium. Hotel Murano, Tacoma, Washington. April 14-16, 2015.

Randall, Robert J. Characterization of the Red Bluff Landslide, Greater Cascade Landslide Complex, Columbia River Gorge, Washington. Diss. Portland State University, 2012.

The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. 2005. U of Nebraska Press / U of Nebraska- Lincoln Libraries-Electronic Text Center. 5 Oct. 2005 . Accessed 22 Nov. 2017.

FURTHER READING

Aguilar Sr., George W. “The Bridge of the Gods.” In When the River Ran Wild! Indian Traditions on the Mid-Columbia and the Warm Springs Reservation. Portland, OR: Oregon Historical Society, 2005. 235.

Atwell, Jim. Tahmahnaw. The Bridge of the Gods. Skamania, WA: Tahlkie Books, 1973.

Clark, Ella E. In Indian Legends of the Pacific Northwest. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1953.

Condon, Thomas. The Two Islands and What Came of Them. Portland, OR: J. K. Gill Company, 1902. Chapter 12.

Judson, Katharine B. Myths and Legends of the Pacific Northwest. 1910. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1997.

ILLUSTRATIONS

Figure 1: Krause, Stefan. “The present-day ‘Bridge of the Gods’ showing a mural of the former natural bridge bearing the same name.” 15 July 2016. JPEG. © Stefan Krause

Figure 2: James, Jimmie. The Legendary “Bridge of the Gods”. 1963, charcoal, Northwest Art Mall, Inc., Gresham, OR, 2009.

Figure 3: Cole, Thomas. Evening in Arcady. 1843, oil on canvas, Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, CT. WikiArt.org - Visual Art Encyclopedia. Public Domain. Accessed 22 Nov. 2017.