Bear Lodge/Devils Tower

by Stefan Livo, 01/16/2019.

Summary

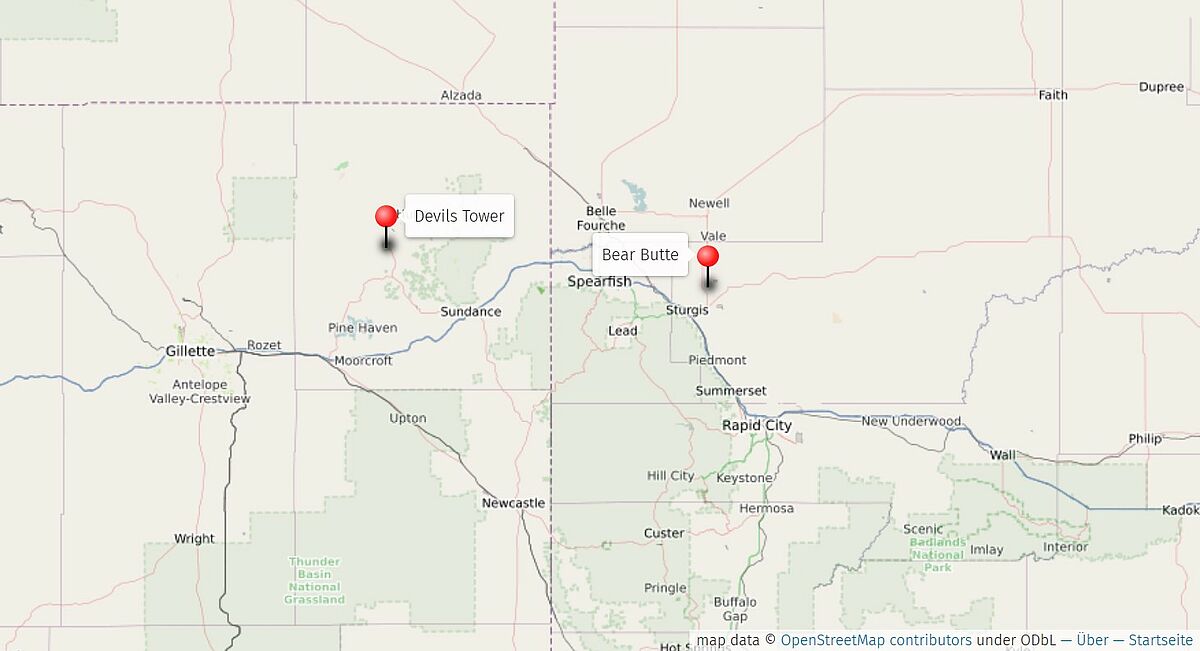

In Northeastern Wyoming a lonely rock composed of peculiar columns towers over the surrounding land. Traditional stories of the Lakota, Cheyenne, Kiowa and other Native American nations and tribes remember how the mountain was once pushed towards the sky to save a group of their ancestors. [teaser] Tribal traditions variously describe how a group of girls or warriors climbed on a small hill to flee from a giant bear and how the Great Spirit pushed up the hill to its present elevation. The bear clawed the walls of the rock tower in vain, leaving behind its marks in the shape of distinct crevices or columns. Geologically speaking a laccolithic butte, ‘Bear Lodge’ received its name from these stories. What are the landmark stories behind Bear Lodge and how did it end up with the name ‘Devils Tower’?

Bear Lodge is a sacred site to many Native American nations and tribes. The Lakota call it “Mato Tipilia (home of the bears)” (LaPointe, 65), the Arapahoe “Bear’s Tipi”, the Cheyenne “Na Kovehe (Bear Lodge)”, the Crow “Bear’s House”, and the Kiowa Tso-aa (Tree-Rock) (National Park Service, “First Stories”). The traditional stories of the local tribes describe the origin and the spiritual significance of the solitary rock. Although there are a few differences between the various oral traditions, the stories of Bear Lodge generally describe how a low hill is pushed up until it reaches the lonely heights of today’s landmark, and how a bear tries to scale the towering rock in vain, leaving behind crevices along the rock with its claws.

One of the most famous traditions is related by Lakota author James LaPointe. In his story, a caravan of Teton Lakota travel toward the Black Hills (Paha Sapa) to harvest fruit and other food. When the caravan arrives in the rugged terrain of the Black Hills they also find numerous bears in the piney forests. One day, seven little girls wander off and get separated from the group. Search parties look for the girls and find them surrounded by hungry bears at a distance. Too far away to help the screaming girls, the search party has to watch how the bears close in on the girls. Suddenly, a voice from the skies tells the girls to climb a little hill nearby. The girls do as the voice tells them and gather on the little knoll.

“The situation appeared hopeless, but like the wrath of thunder, the earth shook and groaned as the little knoll, commanded by a strange voice, began to rise out of the ground, carrying the children high into the air. Higher and higher the mound rose, as the frustrated bears growled and clawed at its sides. Sharp pieces of rock broke away from the rising spire and crashed down upon the angry bears.” (LaPointe, 67)

The girls are saved and the bears are buried under molten rocks falling down. The voice in the skies, Taku Wakan (the Creator), sends colorful birds, who pick up the girls from the rock’s top and fly them back to their mothers.

Stories from the Arapahoe and Kiowa talk about the connection between Bear Lodge and the constellation of the Pleiades (National Park Service, “First Stories”). In the Kiowa version, told by Kiowa warrior I-See-Many-Camp-Fire-Places in 1897, a group of seven girls find themselves in a similar pickle. Surrounded by bears the girls jump on a rock nearby and ask it to take pity on them.

The rock heard them and began to grow upwards, pushing the girls higher and higher. When the bears jumped to reach the girls, they scratched the rock, broke their claws, and fell on the ground. The rock rose higher and higher, the bears still jumped at the girls until they were pushed up into the sky, where they now are, seven little stars in a group (The Pleiades). (National Park Service, “First Stories”)

The traditional stories of the Cheyenne above all remember Bear Lodge as the dying place of their culture hero Sweet Medicine, who had brought the four arrows to the tribe and who is the originator of important laws, a warrior society, and civil institutions. The Cheyenne remember yet another story about the origin of Bear Lodge. In this version, told by Young-Bird from the Lame Deer Reservation, a group of Cheyenne camps near Na Kovehe (Bear Lodge). The wife of one of the men leaves the camp repeatedly for a long time and her husband grows suspicious. Eventually, the husband discovers claw marks on his wife’s back and she admits that a lonely bear of enormous size has courted her. She leads her husband to the bear and is transformed into a bear herself when the bear claws her. Unable to kill the giant bear alone, the husband gathers six fellow warriors. Yet even with their help, the bear is too powerful and the men pray to the Great Spirit for help.

In answer to their prayers, the rock began to grow up out of the ground and when it stopped it was very high. The bear jumped at the men and on the fourth jump his claws were on the top. The Great Spirit had helped the men and now they had great courage and they shot the bear and killed him. When the bear fell backwards and pushed the big rock, the big rock leaned. After that the bear-woman made this big rock her home, so the Cheyennes call it “Bear Lodge.” (National Park Service, “First Stories”).

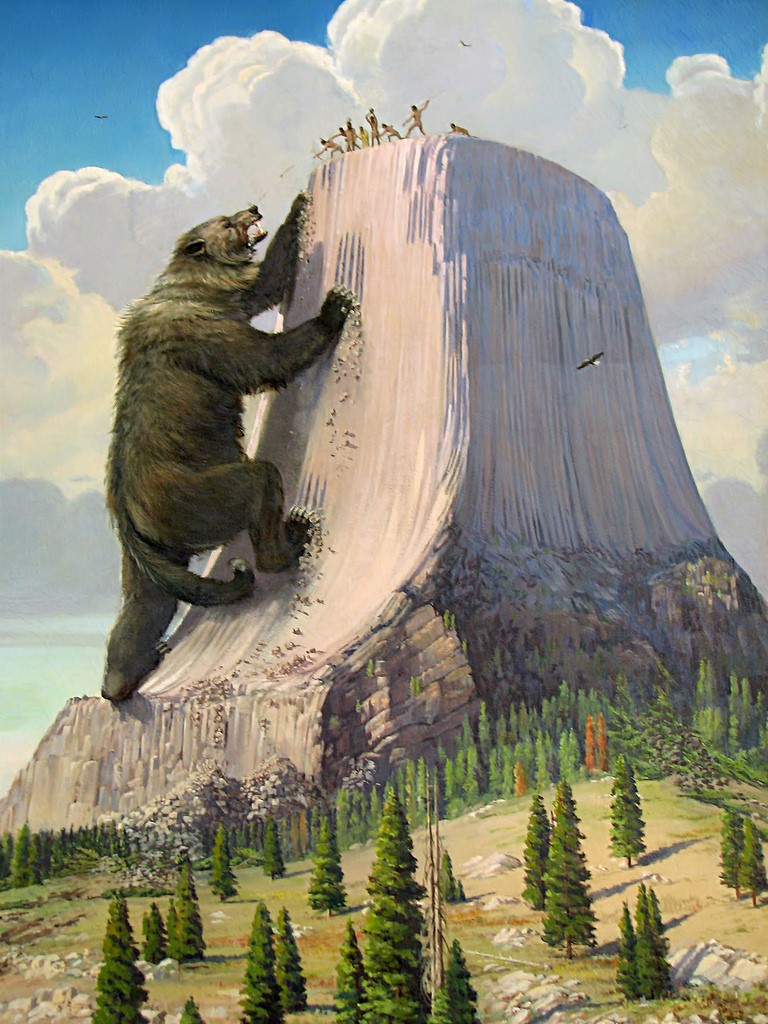

Other traditional stories about the origin of Bear Lodge appear in Wooden Leg’s A Warrior Who Fought Custer (1931). The book, edited by Thomas B. Marquis, is based on interviews with the Northern Cheyenne Wooden Leg, in which he talks about his experiences as a warrior and the traditions of the Cheyenne. Wooden Leg recounts a few stories told to him by old Cheyenne knowledge keepers. One of these stories about the giant bear, sometimes called Mato, was famously illustrated in a painting by Herbert A. Collins in 1936.

Naming and Appropriation

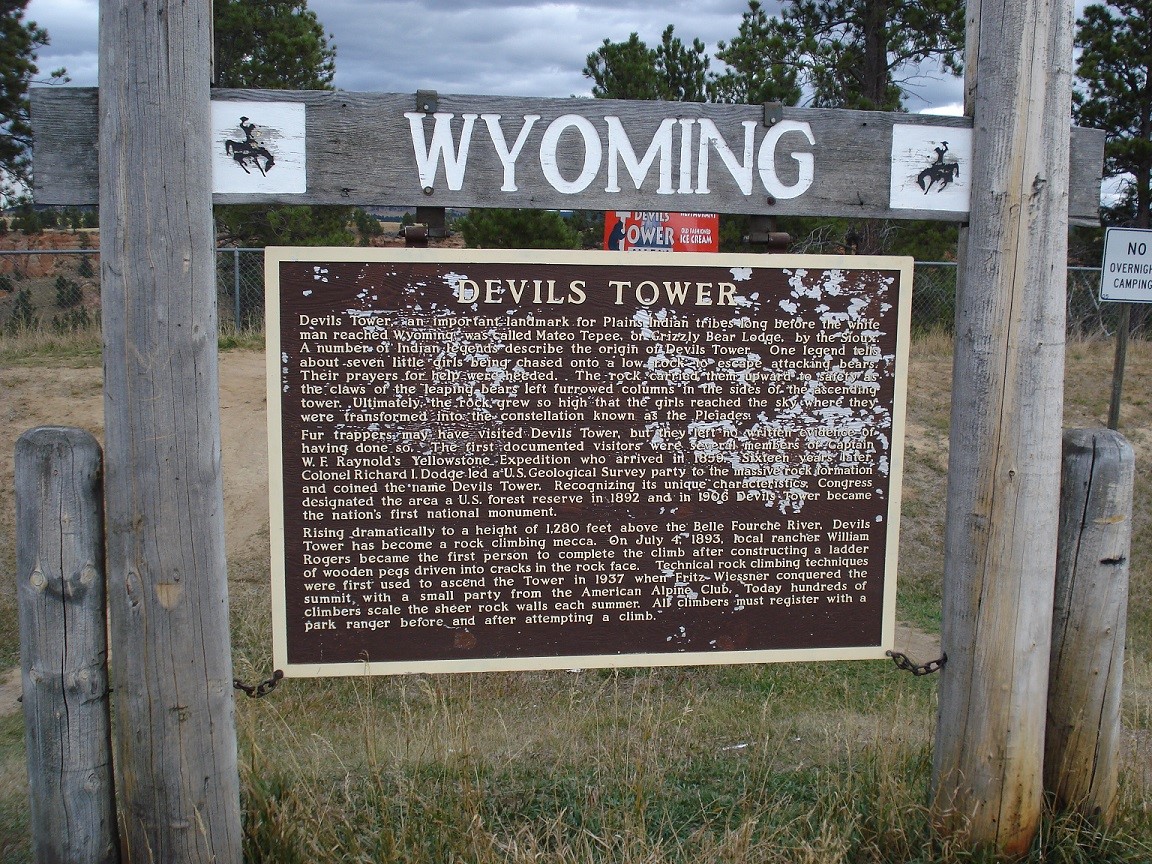

When Wooden Leg shared his knowledge with Marquis, he also emphasized, “As far back as I can remember, all of the Indians called this stone Bear Tepee or Bear Lodge” (54). This poses the question how the landmark ended up with the name ‘Devils Tower’. The question takes us back to the late nineteenth century, when European-Americans first became aware of the lonely rock spire. As the story unfolds, Devils Tower/Bear Lodge moves into the center of debates regarding the establishment of national monuments and the appropriation of sites sacred to Native Americans: Fur traders, settlers, and military expeditions traveled through the land of the Black Hills at least as early as the 1850s (National Park Service, “First Explorers”). Some of them knew about the Black Hills, the Yellowstone, and Bear Lodge—as the landmark was commonly called and marked on maps with respect to the Indigenous names—but the earliest written account dates to the 1870s. In 1874, the infamous General George Armstrong Custer went on an expedition to the Black Hills and soon announced the discovery of gold in the region. Just a year later, the United States Geological Survey (USGS) led another expedition to the area to ascertain Custer’s claims and they came across Bear Lodge. In his publication The Black Hills (1876), expedition leader Colonel Richard Irving Dodge notes, “The Indians call this shaft ‘The Bad God’s Tower,’ a name adopted, with proper modification, by our surveyors” (Dodge, 95). Unfortunately, Dodge misunderstood or mistranslated the name offered by his Indigenous informants, which led to the misleading name ‘Devil’s Tower.’

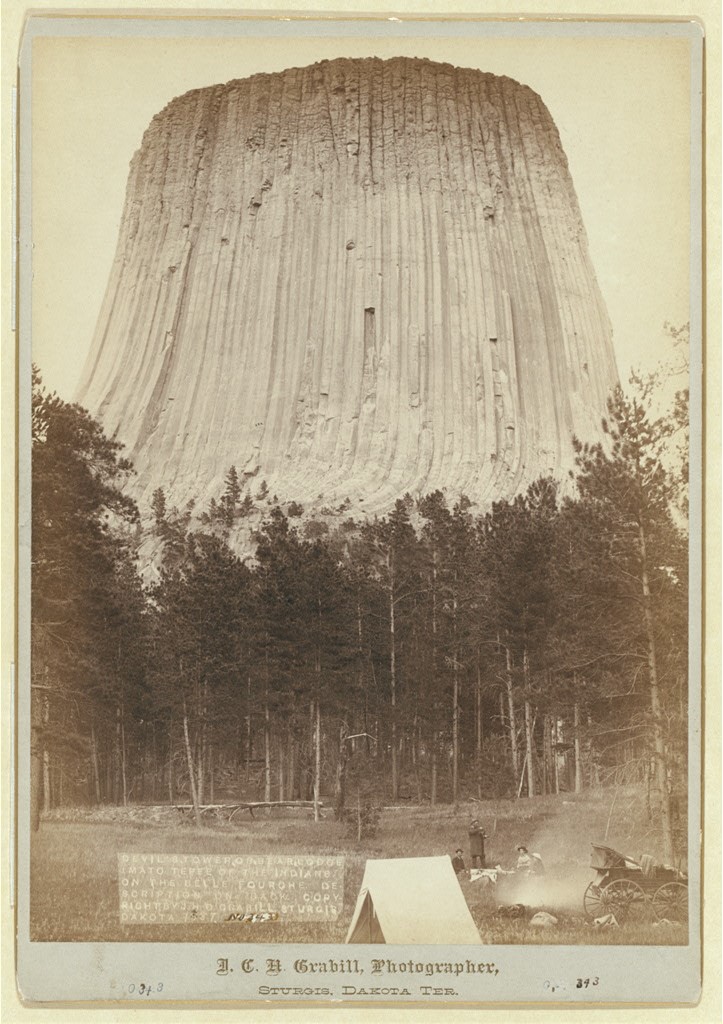

Most of the local Native American tribes named the mountain based on their stories about a giant bear. Thus, the name ‘Devil’s Tower’ was unrelated to their traditions, which do not feature any “bad gods” or devils. However, Dodge’s name for the rock became very popular among the American public at the end of the nineteenth century, quite in keeping with the demonization of Indigenous religion which the colonial state intended to replace with the teachings of Christianity. When Wyoming finally became a state in 1890, it officially changed the original name ‘Bear Lodge’ to ‘Devils Tower’ (National Park Service, “First Explorers”). In 1906, Congress passed the Antiquities Act, which gave the President of the United States the power to designate certain sites as ‘national monuments’. In the same year, President Theodore Roosevelt established “Devils Tower” as the first national monument of the USA. His main motivation to do so was not related to his interest in Native American culture, but to his concern with the conservation of the USA’s natural grandeur. This process of establishing Bear Lodge/Devils Tower as a prime example for the sublimity of the American West was decades in the making, as indicated by earlier photography (e.g. by John Grabill). The significance of “Devils Tower” was re-appropriated from that of a sacred site and place of creation to a geologic oddity and conspicuous landmark. Within a few years, the United States surveyed, settled, and claimed the area of Bear Lodge.

Bear Lodge is an important sacred place in more than twenty-three tribal creation stories (Dustin et al., 81) and has been traditionally connected to cultural practices like the Sun Dance (LaPointe, 68-70) and vision quests, but at the time of its establishment as the Devils Tower national monument none of this mattered. At the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth century, the American government banned many of these Native American religious practices in the wake of assimilation policies (Cross and Brenneman, 8). For the greater part of the twentieth century, Indigenous tribes did not have the political or legal support to fight for their traditional rights and had to deal with termination and relocation policies instead.

Meanwhile, the rock tower attracted many tourists, but it experienced yet another increase in visitors after the release of Steven Spielberg’s movie Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977). In the movie, “Devils Tower” becomes a landing zone for UFOs and extraterrestrials: this is how the colonial society integrates the landmark into its own story-making culture – a culture of fear, it seems, of suffering the same fate as America’s indigenous inhabitants, now by an invasion from outer space. The movie was a great success and inspired large numbers of tourists and climbers to visit “Devils Tower.” Starting in the 1970s and 80s more than 6,000 climbers scaled the walls of the rock every year, often using invasive technologies like bolts and pitons (Dustin et al., 81). Furthermore, climbers mostly came to “Devils Tower” in the summer months when the local Native American tribes performed traditional ceremonies at the rock. These contradicting and mutually exclusive ways of ‘owning’ the site led to a number of legal conflicts (e.g. Burton and Ruppert, Cross and Brenneman).

The legal battles about how to protect and use Bear Lodge eventually produced solutions that considered Indigenous perspectives as well. After the enactment of the American Indian Religious Freedom Act (1978) and with the help of the National Park Service (NPS), the local tribes stated their case for the respectful treatment of the landmark. The NPS set up a work group that brought together representatives of the conflicting sides and issued a Final Climbing Management Plan (FCMP) in 1995. The plan sought to prohibit the use of climbing techniques that could damage the rock and “implemented the voluntary June closure to climbing” (Cross and Brenneman, 8), the most prominent month for Indigenous ceremonial practices at the rock. But the percentage of compliance with the ban was only at roughly 85 percent in 1996 (Linge, 313), and many climbers still disregard the ban to this very day.

Additionally, representatives of the Wyoming state government have tried hard to retain “Devils Tower” as the official name of the landmark, defending it against critics who in the 1990s demanded to restore the traditional name ‘Bear Lodge’ to the rock. In 1996, Barbara Cubin, representative of the 104th Congress of Wyoming, introduced a bill that sought the retention of the name ‘Devils Tower’ (Burton and Ruppert, 203). The bill did not pass. In the following years, various Indigenous claimants took legal steps to change the name back to ‘Bear Lodge’. So far, none of their requests has been successful. Instead, politicians like Liz Cheney—member of Wyoming’s at-large Congressional District and daughter of former Vice President Dick Cheney—continue to draft bills to retain the name ‘Devils Tower’ and claim the landmark as one of the “state’s most beautiful and sacred geological features” (Buckrail, March 14, 2018). Less than 150 years after the first European-Americans laid eyes on the lonely rock tower, Western society has claimed the site of Bear Lodge, its traditional name, and its very sacredness – but it could not claim its stories.

The Stories Remain

Landmark stories about Bear Lodge belong to the category of what Dorothy Vitaliano terms “landform lore:” etiological stories about conspicuous landscape features whose formation precedes the appearance of man in the region (37). Bear Lodge/“Devils Tower” has been ‘storied’ in vastly different ways by the cultures involved. The conflict about the oppositional cultural meaning of the rock – as a sacred place, as the place of the Devil – speaks volumes about the different ideological approaches to the land in Indigenous and colonial societies. It highlights the importance and value of Indigenous oral tradition and landmark stories in general. Colonial practices such as the dispossession, renaming, and re-appropriation of Indigenous places have threatened (and still do) the cultures of Indigenous peoples and the ties to their traditional territories and beliefs. Stories like that of “Devils Tower” and Crater Lake show how spaces sacred to Native Americans have been claimed by Western agents such as explorers, settlers, climbers, tourists, conservationists, scientists – and storytellers (including filmmakers). While many of them acknowledge that these places are sacred to many Natives American tribes, others assume the narrow Western perspective of place as something to be mapped and possessed. But regardless of these claims and perspectives, landmark stories such as the Indigenous oral traditions quoted in this section establish a relationship beyond the reach of colonial appropriation. Certainly, Native American traditional texts have been mistranslated and misinterpreted, but the very stories remembered by Indigenous communities establish a tie that is unique in its depth, complexity, and age. These landmark stories amount to a knowledge archive that makes sense of the origin and significance of sites, provide guidelines on the relationship between a place and its inhabitants, and offers ecological knowledge about a specific environment. Furthermore, these stories help Native American communities to preserve their traditional ties with the land. Although these ties have been repeatedly threatened and disrupted in colonial times, traditional stories have helped Native Americans to protect their unique relationship to the land, and they continue to do so.

WORKS CITED

Burton, Lloyd and David Ruppert. “Bear’s Lodge or Devils Tower: Intercultural Relations, Legal Pluralism, and the Management of Sacred Sites on Public Lands.” Cornell Journal of Law and Public Policy 8, 2 (1999). 201-247.

“Congresswoman Cheney Protects Devils Tower from Name Change.” Buckrail, March 14, 2018. buckrail.com/congresswoman-cheney-protects-devils-tower-from-name-change/. Accessed January 16, 2019.

Cross, Raymond and Elizabeth Brenneman. “Devils Tower at the Crossroads: The National Park Service and the Preservation of Native American Cultural Resources in the 21st Century.” Public Land and Resources Law Review 18 (1997). 5-45.

Dodge, Richard I. The Black Hills: A Minute Description of the Routes, Scenery, Soil, Climate, Timber, Gold, Geology, Zoology, Etc. New York: James Miller, 1876.

Dustin, Daniel L., Ingrid E. Schneider, Leo H. McAvoy, and Arthur N. Frakt. „Cross-Cultural Claims on Devils Tower National Monument: A Case Study.” Leisure Sciences 24 (2002). 79–88.

LaPointe, James. Legends of the Lakota. San Francisco: The Indian Historian Press, 1976.

Linge, George. “Ensuring the Full Freedom of Religion on Public Lands: Devils Tower and the Protection of Indian Sacred Sites.” Boston College Environmental Affairs Law Review 27, 2 (2000). 307-338.

National Park Service. “First Explorers.” Devils Tower National Monument. www.nps.gov/deto/learn/historyculture/early-exploration.htm. Accessed January 16, 2019.

National Park Service. “First Stories.” Devils Tower National Monument. www.nps.gov/deto/learn/historyculture/first-stories.htm. Accessed January 16, 2019.

Vitaliano, Dorothy B. Legends of the Earth. Their Geologic Origins. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1973.

Wooden Leg. A Warrior Who Fought Custer. Ed. Thomas B. Marquis. Minneapolis: The Midwest Company, 1931.

ILLUSTRATIONS

Figure 1: Livo, Stefan. “Devils Tower.” 2011. JPEG.

Figure 2: Collins, Herbert A. “Devils Tower Bear Legend.” 1936. Painting. National Park Service, Centennial One Object Exhibit. Devils Tower National Monument.

Figure 3: Grabill, John C.H. “Devil’s Tower or Bear Lodge (Mato [i.e. Mateo] Tepee of the Indians), on the Belle Fourche.” 1887. Photograph. Source: Library of Congress [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons. Wikimedia Foundation. Web. 24 January 2019. <<https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Devil%27s_Tower_or_Bear_Lodge_(Mato_(i.e._Mateo)_Tepee_of_the_Indians),_on_the_Belle_Fourche._Description_on_back_-_J.C.H._Grabill,_photographer,_Sturgis,_Dakota_Terr._LCCN99613929.jpg>>

Figure 4: Livo, Stefan. “Devils Tower Sign.” 2011. JPEG.