The Antiquities Act of 1906

by Alexander Bräuer, 03/06/2016.

Summary

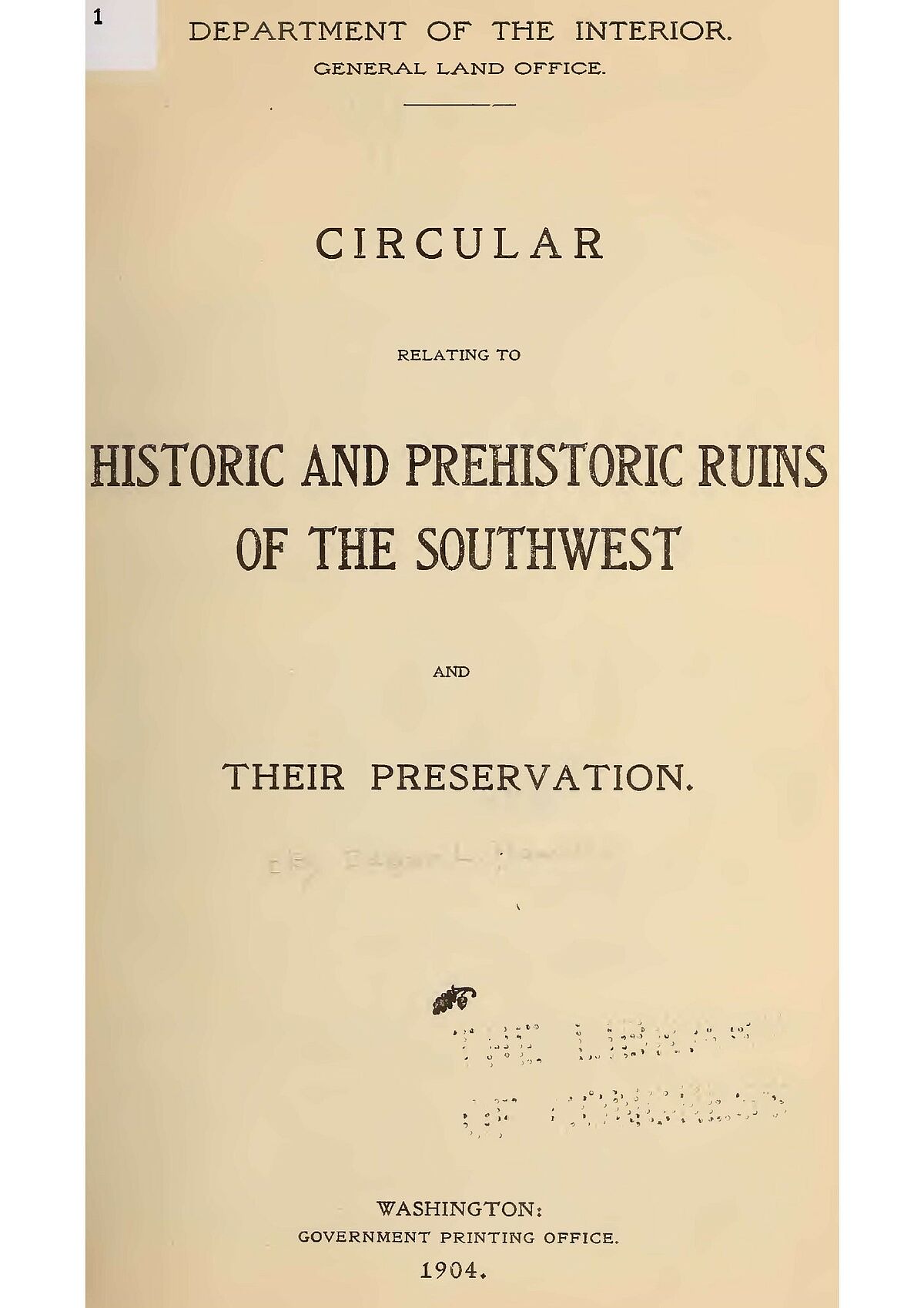

The beginning of the 20th century witnessed increased lobbying efforts by Edgar L. Hewett, an anthropologist and archaeologist, for the establishment of protected areas against the robbery of antique potteries on government land. In 1906, the Congress reacted by passing the Antiquities Act. The Act gave the President the power to declare "… historic landmarks, historic and prehistoric structures, and other objects of historic or scientific interest that are situated upon the lands owned or controlled by the Government of the United States to be national monuments." Therefore, in the following years Theodore Roosevelt could easily declare a number of national monuments to protect ruins on government land and in the territories of the Southwest. This represented a power shift in the political sphere because in contrast to national monuments, national parks could only be created by Congress. The following article tries to reconstruct the emergence of the Act out of an influential report, a “Circular relating to Historic and Prehistoric Ruins of the Southwest and their Preservation,” initiated and largely written by Hewett in 1904. It furthermore seeks to explore what role ideas and constructions of an American Antiquity played in the promotion and ultimately completion of the Act.

The beginning of the 20th century witnessed increased lobbying efforts by Edgar L. Hewett, an anthropologist and archaeologist, for the establishment of protected areas against the robbery of antique potteries on government land. In 1906, the Congress reacted by passing the Antiquities Act. The Act gave the President the power to declare “… historic landmarks, historic and prehistoric structures, and other objects of historic or scientific interest that are situated upon the lands owned or controlled by the Government of the United States to be national monuments.”[1] Therefore, in the following years Theodore Roosevelt could easily declare a number of national monuments to protect ruins on government land and in the territories of the Southwest. This represented a power shift in the political sphere because in contrast to national monuments, national parks could only be created by Congress. The following article tries to reconstruct the emergence of the Act out of an influential report, a “Circular relating to Historic and Prehistoric Ruins of the Southwest and their Preservation,” initiated and largely written by Hewett in 1904. It furthermore seeks to explore what role ideas and constructions of an American Antiquity played in the promotion and ultimately completion of the Act.

Edward L. Hewett migrated from Colorado to New Mexico in the 1890s and quickly became fascinated with the remains of Native American cultures in the area. From the start he proposed a national park to protect the ruins on the Pajarito Plateau, a plan resisted by local ranchers. Hewett worked as the president of the Normal School in New Mexico and as such recognized early the importance of connections to powerful politicians. After stepping down from his position at the Normal School, he earned a doctorate in anthropology and continued to lobby for his plans to protect the ruins. In 1902, he served as a guide to John F. Lacey, a Congressman from Iowa who wanted to collect information about the robbery and trade of pottery from the ruins. Two years earlier, Hewett had travelled to Washington, D.C. in order to establish connections to the influential anthropologist Alice Cunningham Fletcher. With the help of his contacts in Washington, D.C., he started a second attempt to promote areas of protection for Native American ruins in 1904 and sent a report about the “Prehistoric Ruins of the Southwest and their Preservation” to the General Land Office. This report would become crucial for the passage of the Antiquities Act in 1906. Since the key points of the report were basically transferred to the Antiquities Act, the following parts of this article will take a closer look at the argument in the report.

The Value of Native American Ruins

The first and most crucial task of the report by Hewett was to clarify the relationship between the “prehistory” of Native Americans and the contemporary United States. The Congressmen had to accept that Native American ruins represented objects worth of preservation. Therefore, Hewett proclaimed quite prominently on the first pages of his report about Native American ruins: “We now know them to be very numerous and of great value. The question of the preservation of this vast treasury of information relative to our prehistoric tribes has come to be a matter of much concern to the American people.”[2] The creation of an American Antiquity, meaning the connection between Native American “prehistory” and the contemporary history of the United States, constituted a precondition for the enactment of areas of protection because the perceptional value of preservation needed to be higher than the profit of economic exploitation by other uses of the areas. As Hewett knew from earlier conflicts with ranchers on the Pajarito Plateau, areas of protection had local enemies who sought to build their economic livelihood on the resources of the land. For this reason, his report repeatedly underlines three points: the high value of the proposed areas for historical knowledge, the low value of the remote areas for other economic enterprises, and that the protected areas only needed to encompass the archaeological sites and their immediate surroundings.[3]

Scientific Value

For Hewett the value of the ruins resided in their function as a “vast treasure of information,” a rather ambiguous category that demanded for a further explanation. Later, he elaborates that every ruin “can contribute something to the advancement of knowledge, and hence is worthy of preservation.”[4] The worth of the ruins was established not via their material value but rather via their function as vehicles of knowledge – an empirical treasure – that proper scientific research could reveal, interpret and translate to the American people, preferably in controllable environments like schools and museums. The areas of protection would create the best environment for such a process of knowledge collection that should be realized through extensive field work and assisted by modern archaeological methods – for example with photographs.[5] The knowledge transfer becomes even more important when we keep in mind that at the beginning of the20th century the remote archaeological sites themselves had, other than today, been inaccessible for the large majority of the American people. Public access to the ruins for American people and travelers from abroad – and the economic value generated through their visit – would remain a project for future generations.[6]

The Value of the Beautiful

However, another even more ambiguous element played an important role in the promotion of Native American ruins: beauty. Beauty, not to say the sublime mysteriousness of the ancient ruins, added to the value of these archeological sites and gave them another unique dimension that could only be experienced by visiting the sites: “… these regions may be made a perpetual source of education and enjoyment …”[7] It is not surprising that “enjoyment” and “scenic beauty” became more prominent when Hewitt directly promoted the creation of a specific form of area or protection, the National Park, for ruins, exemplified particularly in the passage on his favorite project: the Pajarito Plateau.[8] The value of national parks usually was generated through beauty of the landscape, or other geological or natural features. This aspect reflects like no other the Hewett’s personal commitment to the protection of Native American ruins.

A Case of Emergency

Finally, Hewett needed to address a rather formal albeit crucial point for the success of his campaign: the political dimension. The protection of the proposed areas was already possible with the laws in place before the Antiquities Act. However, the creation of national parks by Congress required numerous powerful resources, a deep knowledge of the political system and a lot of time. These conditions were not feasible for the numerous sites Hewett desired to protect with his campaign. Therefore, a new mechanism for the creation of areas of protection needed to bypass Congress with its complex, difficult and time-consuming procedures, and to transfer the power to another more accessible political entity, the president, Theodore Roosevelt himself, who was a vivid supporter of national parks

The politically experienced Hewett certainly took this formal point into consideration when writing his report. Therefore, he presented his campaign as the result of a case of emergency. The pottery trade provided Hewett with the necessary urgency. As he explains prominently at the beginning of his report, Native American potteries were increasingly removed from the ruins by private entrepreneurs destroying in the process valuable information about American history while at the same time generating private wealth from plundering government land.[9] Furthermore, in his list of the areas proposed for protection, every description of an area begins with the – often alarming – state of the local pottery traffic. One of his most important political achievement was probably the acknowledgement of the urgency by the administration as expressed in a reply to the report by W. A. Richards, Commissioner of the General Land Office: “It is evident that immediate and effective measures should be taken by the Government to protect regions containing objects of such great value to the ethnological history of this country and to other scientific studies.”[10] However, Hewett aimed not for a downright prevention of removals of artifacts from the ruins, rather he tried to limit the right to remove artifacts to a certain group of persons, licensed scientists, who, following his argument, were the only group able to retrieve valuable information from the ruins.[11] After the valuable information was retrieved by scientists, areas could indeed lose their protection: “I am also heartily in accord with your recommendation that, while many of the tracts containing ruins and other objects of interest need only to be temporarily withdrawn and protected until the ruins and objects thereon have been satisfactorily examined and utilized.”[12] Overall, Hewett emerged victorious in both, the conveyance of urgency and the resulting implementation of short and simple political procedures to fight the urgency.

Ironically, contemporary Native Americans were part of the problem because of their participation in the pottery trade and their vicinity to the protected areas.[13] And since Native Americans at the same time were hardly allowed the necessary education to take part in the scientific removal, other than as cheap workers, careful instructions to the local tribes – and if necessary the power of law – were seen as inevitable for a successful implementation of areas of protection.[14] The Antiquities Act of 1906 was ultimately designed to absorb Native American ruins and “prehistory” into the master narrative of an American history without integrating living Native Americans into America.

NOTES

[1] http://www.nps.gov/history/local-law/anti1906.htm, accessed 03/03/2016.

[2] Hewett, Edgar L.. Historic and Prehistoric Ruins of the Southwest and their Preservation. Washington: Govt. Print. Off., 1904, p. 4.

[3] Ibid., p. 12.

[4] Ibid., p. 3.

[5] Ibid., p. 7.

[6] Ibid., p. 4 & 7.

[7] Ibid., p. 4.

[8] Ibid., p. 6.

[9] Ibid., p. 2.

[10] Ibid., p. 13.

[11] Ibid., p. 4.

[12] Ibid., p. 13.

[13] Ibid., p. 9.

[14] Ibid., p. 15.

ILLUSTRATIONS

Figure 1: Edgar L. Hewett, influential lobbyist for the Antiquities Act. Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edgar_Lee_Hewett#/media/File:Edgar_lee_hewett1.jpg; accessed 03/03/2016.

Figure 2: Front Page of an influential report by Edgar L. Hewett promoting the protection of Antiquities in 1904. Source: Hewett, Edgar L.. Historic and Prehistoric Ruins of the Southwest and their Preservation. Washington: Govt. Print. Off., 1904.

Figure 3: Devils Tower, the first National Monument under the Antiquities Act, declared by President Theodore Roosevelt in 1906. Source: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Devils_Tower_National_Monument#/media/File:Jeff_Fennell_-_Devils_Tower_%28by%29.jpg, accessed 03/03/2016.

Figure 4: Source: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:El_Morro_National_Monument, accessed 03/29/2017.

Figure 5: Source: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Montezuma_Castle_National_Monument, accessed 03/29/2017.

Figure 6: Source: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tonto_National_Monument, accessed 03/29/2017.

Figure 7: Source: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Gila_Cliff_Dwellings_National_Monument, accessed 03/29/2017.