Nanih Waiya – The Mother Mound

by Stefan Krause, 08/01/2018.

Summary

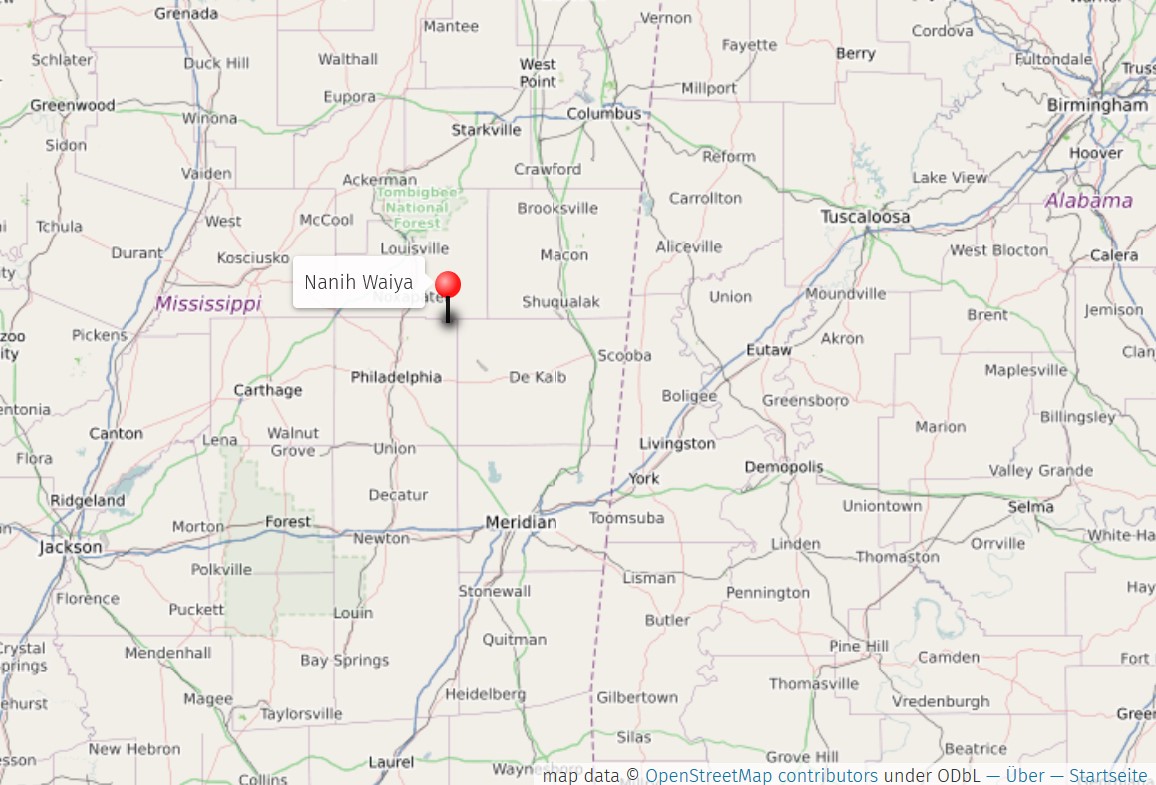

The indigenous peoples of North America have built earthen mounds at least as early as 3,500 BC (see Watson Brake). Most of these mounds have been destroyed or pillaged in times of colonial contact, but some have been preserved. Nanih Waiya is one of these earthworks, and it tells the story of an entire nation. The man-made mound in Winston County, Mississippi, was probably built in what Western archaeology has dubbed the Middle Woodland Period between 0-300 AD (Carleton). It is a sacred place for the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians, who, to this day, remember the story of the mound in various oral traditions. Over time, Nanih Waiya has become a landmark preserving the Choctaws’ link to their homeland, their ancestors, and their traditional stories.

Nanih Waiya features prominently in Choctaw oral tradition, appearing in migration stories, stories of origin, and many others. The name variously translates into “leaning hill”, “stooping hill” (Carleton) or “mountain that produces” (Nabokov, 50). Yet, curiously, the name Nanih Waiya has been given to two earthen mounds near Noxapater, Mississippi. One of them is located in Mississippi’s Winston County, while the other lesser-known mound has a cave (Nanih Waiya Cave Mound) and is located in Neshoba County. The following text analyzes the stories of the two mounds and the Choctaw Nation’s connection to their mother mound.

The first European-American who claims to have seen Nanih Waiya was the Irishman James Adair. He traveled through Choctaw land in the 1760s and wrote down his observations in his The History of the American Indians (1775). Adair mentions two identically named mounds in close proximity of each other, but does not give any detail on the significance of the structures. Adair also states that the local tribe (Choctaw) call the mounds “Nanne Yah, ‘the hills, or mounts [sic!] of God’” (378).

“About 12 miles from the upper northern parts of the Choktah country, there stand on a level tract of land, the north-side of a creek, and within arrow-shot of it, two oblong mounds of earth, which were old garrisons, in an equal direction with each other, and about two arrow-shots apart.” (Adair, 378)

Almost a century later, historian and pioneer Gideon Lincecum was one of the first European-Americans to write down the story behind Nanih Waiya.[1] Lincecum visited the site in 1843 and published the Traditional History of the Chahta Nation in 1861. The story describes how, long ago, a group of Choctaw[2] journeyed through North America looking for a fertile place for a winter encampment. The journey was long and rough – the group of Choctaw lost many people along the way and had to carry their remains with them. Finally, the group’s scouts returned with good news. Guided by the leader’s pole – a pole which would determine their course of travel by tilting toward one direction or another – they found a promising place for an encampment, with good lands and at the junction of three creeks.

“One end or side of the encampment, lay along the elevated ground bordering the low lands on the west side of the middle creek. Just above the uppermost camps, and overhanging the creek, was a steep little hill with a hole in one side. As it leaned towards the creek, the people called it the leaning hill (nunih waya). From this little hill the encampment took its name, ‘Nuni Waya,’ by which name it is known to this day.” (Lincecum, 523)

Soon the group of Choctaw started to argue whether it would be better to stay in the area and to find a resting place for the bones of their ancestors or if they should venture on. While the spiritual leaders argued that the people should continue to carry around the bones of their forefathers, the chief disagreed and – in a secret meeting with the people of the tribe – suggested to bury the bones collectively in one big mound. The people supported the chief’s plan and the group of Choctaw built an enormous burial mound for their ancestors. Henceforth, the Choctaw buried their dead in big mounds. If hunters died too far out in the woods to have their remains returned to the camp, it was common practice to bury them near the spot of their death in a small mound. Lincecum also explains that larger mounds with single burials were the work of mourning wives and their children who piled up dirt on their fathers’ graves until they would run out of food and energy. According to Lincecum’s version of the Choctaw tradition, “Nuni Waya” (Nanih Waiya) mound thus became the namesake and starting point of the grave mound tradition (534).

American historian Henry S. Halbert was told another version of the journey of the Choctaw Nation’s ancestors and their settlement at Nanih Waiya by Peter Folsom – a Choctaw who had first seen the mound together with his father in 1833. Folsom describes how the ancestors of the Choctaw and Chickasaw traveled eastwards looking for a fertile land. The group was led by a prophet carrying a pole that would guide the people, similar to the one mentioned in Lincecum’s text.

“After the lapse of many moons, they arrived one day at Nanih Waiya. The prophet planted his pole at the base of the mound. The next morning the pole was seen standing erect and stationary. This was interpreted as an omen from the Great Spirit that the long sought-for land was at last found.” (Halbert, 1899: 227)

Halbert also records a different oral tradition following the words of Isaac Pistonatubbee, a member of the Mississippi Choctaw. According to this version, which represents a generic shift from migration story to creation story, the Muscogee, Cherokee, Chickasaw, and Choctaw were all created at Nanih Waiya. The other three tribes came out of the mound first and left the area to settle somewhere else.

“Very long time ago the first creation of men was in Nanih Waiya; and there they were made and there they came forth. The Muscogees first came out of Nanih Waiya, and they then sunned themselves on Nanih Waiya's earthen rampart, and when they got dry they went to the east. […]

The Choctaws fourth and last came out of Nanih Waiya. And they then sunned themselves on the earthen rampart and when they got dry, they did not go anywhere but settled down in this very land and it is the Choctaws' home.” (Halbert, 1901: 269-270)

Two Nanih Waiya Mounds?

Oral traditions variously talk about Nanih Waiya as an ancient encampment or village, a natural mound, a man-made earthwork, a mound with a cave, and a burial mound. Archaeological research has shown that Nanih Waiya used to be a settlement consisting of many earthworks, but most of these have been destroyed due to the European settlers’ agricultural activities. In the late eighteenth century, Adair observed two mounds in the area. They both bear a similar (or even the same) name and traditional stories suggest that they are closely connected.

Anthropologist Peter Nabokov raises the question whether Nanih Waiya Cave Mound is a natural mound possibly “associated with the Creation myth of Choctaw origins, whereas the man-made mound only a few yards away was the site emphasized in their [the Choctaw Nation’s] migration scenario” (49). On the one hand, the assumption is supported by the fact that the creation stories usually talk about the first Choctaws crawling “through a hole or a cave […] into the light of day” (Halbert 1899, 230). The hole in Nanih Waiya Cave Mound is still visible today. On the other hand, even migration stories, such as the one recorded by Lincecum, talk about two mounds – the mound with the hole and name giver of the group’s encampment, and the burial mound constructed by the group to bury their ancestors.

Although stories such as the one recorded by Lincecum show that both mounds play a role in Choctaw tradition, Nanih Waiya in Winston County is generally considered the mother mound by the tribe. The homepage of the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians describes it as the “Heart of the Choctaw People” and highlights the earthwork in Winston County as central to their oral traditions. At the same time, Choctaw Tribal Historic Preservation Officer Ken Carleton acknowledges that stories also suggest that the Choctaw and other tribes “entered the world from a cave near the mound” (emphasis added). This describes the cave and the mound as two independent places of spiritual importance. Whereas the cave is located on the slopes of a natural formation, Nanih Waiya is a man-made earthwork that links the Choctaw to their ancestors.

Intertwined Stories

The story of the Choctaw and of Nanih Waiya are deeply connected. The creation of the great burial mound and the surrounding settlement marks a landmark story that helps the Choctaw preserve their traditions and connection to their ancestors. Stories about Nanih Waiya emphasize the great age of the indigenous presence in the area, but they also remind us of how a landscape can be re-inscribed time and again.

Artifacts found on the surface of the mound indicate that it was built in the so-called Middle Woodland Period (0-300AD). The area of Nanih Waiya had probably been inhabited until 700 AD, but was abandoned during the “Mississippian Period” between 800-1600 AD (Carleton). The Choctaw, being the descendants of the indigenous peoples of the Hopewell and Mississippian culture, have lived in the land of Nanih Waiya for hundreds of years. As confirmed by their oral traditions recorded in the eighteenth and nineteenth century, the Choctaw knew of the great age of the landmark, venerating it as the mother mound of their people. Up to this day, the Choctaw pay their respect to the mound.

Beginning in the late eighteenth century, the Choctaw got in contact with European American settlement and ensuing warfare. Between 1786 and the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek (1830) the Choctaw signed nine treaties with the United States of America (Choctaw Community News, 5). With the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek the Choctaw were eventually forced to cede 11 acres (45,000 km2) of their traditional homeland, in which the mounds are located, and many members of the tribe were removed to regions west of the Mississippi; some refused to leave their mother mound and remained in the area. The land around Nanih Waiya became a state park. Only in 2007, Mississippi Senate Bill 2732 of 2007 granted the transfer of the mound to the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians (Choctaw Community News, 5). In August 2008 the mound was finally returned to the tribe. Since then, the tribe celebrates every second Friday in August as Nanih Waiya Day to commemorate the return of their mother mound.

Over time, the area around Nanih Waiya has therefore become a storied landscape linking the past of the Choctaw and their ancestors with the more recent history of early white explorers and contemporary Euroamerican inhabitants of the state of Mississippi. Nanih Waiya inscribed the surrounding land as settlement of early indigenous peoples, as burial site, as place of origin for the Choctaw and other tribes, as a contested cultural space, as a state park, and as a gathering site for future members of the tribe. The landmark and related traditional stories, as well as the decision to return the place to their stewardship, show the Choctaw (and their ancestors) as the rightful owners of this sacred site. As such, Nanih Waiya serves as a prime example for the significance of Native American oral tradition in the study of America’s deep past.

NOTES

[1] Frenchman Antoine-Simon Le Page du Pratz describes a creation story of the Choctaw in his Histoire de La Louisiane (1758).

[2] Lincecum calls them Choctaw, but it would be more accurate to regard them as the Choctaws’ ancestors.

WORKS CITED

Adair, James. The History of the American Indians. London: Edward and Charles Dilly, 1775.

Carleton, Ken. “Nanih Waiya: Mother Mound of the Choctaw.” The Delta Endangered 1,1 (1996). www.nps.gov/archeology/cg/vol1_num1/mother.htm. Accessed 8 January 2018.

Halbert, Henry S. “Nanih Waiya, the Sacred Mound of the Choctaws.” Publications of the Mississippi Historical Society, Vol. 2. Oxford, MS: Mississippi Historical Society, 1899. 223-234.

Halbert, Henry S. “The Choctaw Creation Legend.” Publications of the Mississippi Historical Society. Vol. 4. Oxford, MS: Mississippi Historical Society, 1901. 267-270.

Lincecum, Gideon. "Choctaw Traditions about Their Settlement in Mississippi and the Origin of Their Mounds." Publications of the Mississippi Historical Society 8 (1904): 521-54.

Nabokov, Peter. Where the Lightning Strikes. The Lives of American Indian Sacred Places. New York: Viking, 2006.

“Nanih Waiya. Heart of the Choctaw People.” Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians. 2016. www.choctaw.org/culture/mound.html. Accessed 8 January 2018.

“Tribe Observes Nanih Waiya Day.” Choctaw Community News. Vol. XLVI, No. 6. July/August 2016. 1, 5.

ILLUSTRATIONS

Figure 1: Phil Konstantin. A photo of Nanih Waiya. 2016. Wikimedia Commons. Wikimedia Foundation. Web. 8 January 2018. commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Nanih_Waiya_By_Phil_Konstantin.jpg.

Figure 2: Henry S. Halbert, Nanih Waiya, the Sacred Pyramid of the Choctaws. 1898. Kindle ed. Mississippi Historical Society, 2017.

Figure 3: Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians. “Choctaw social dances were performed on the grounds of Nanih Waiya.” Choctaw Community News. Vol. XLVI, No. 6. July/August 2016. 1.