Bear Butte – Sacred Mountain of the Plains

by Stefan Krause, 04/23/2018.

Summary

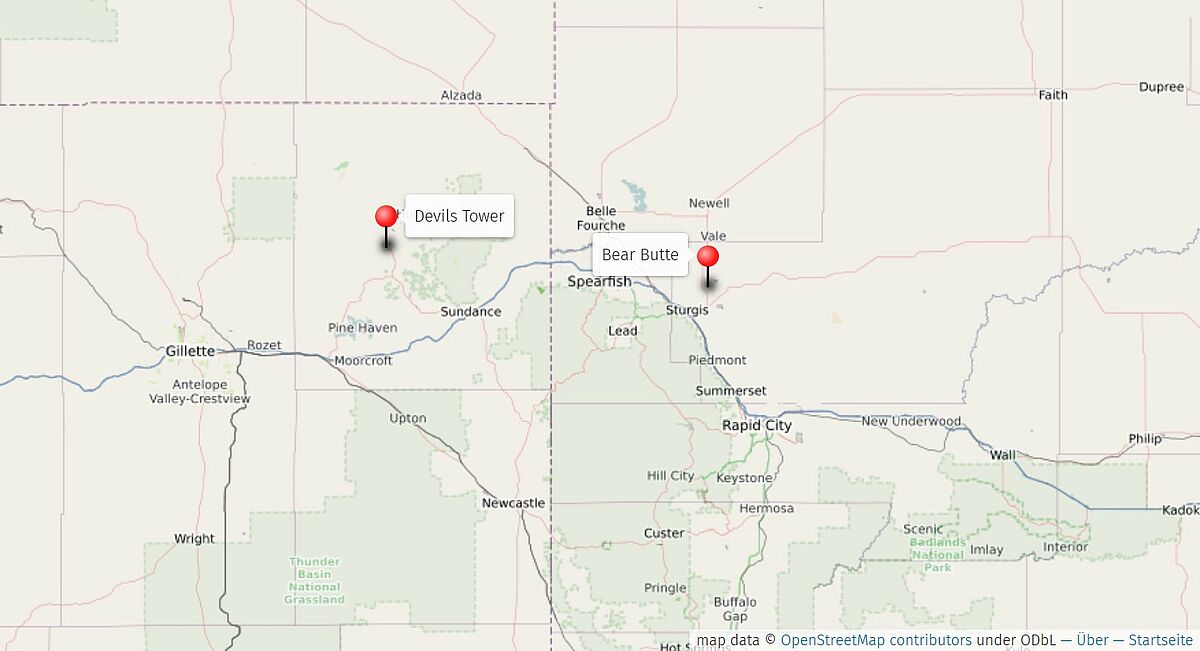

The Black Hills of South Dakota and Wyoming feature prominently in the traditional stories of the Lakota, Cheyenne, Kiowa, and other Native American tribes of the Plains. Yet few, if any, places of the area share the eventful past of Bear Butte site of indigenous creation stories, location of cultural contact, and a major historical landmark. After millennia of indigenous habitation, Bear Butte, which is located in South Dakota just east of the Black Hills, has become a contested place in the post-contact period. In the struggles over land, the very sacredness of the mountain has been questioned. This text looks at the traditional stories testifying to the ancient spiritual significance of Bear Butte, and examines how the mountain has united the tribes of the Plains time and again.

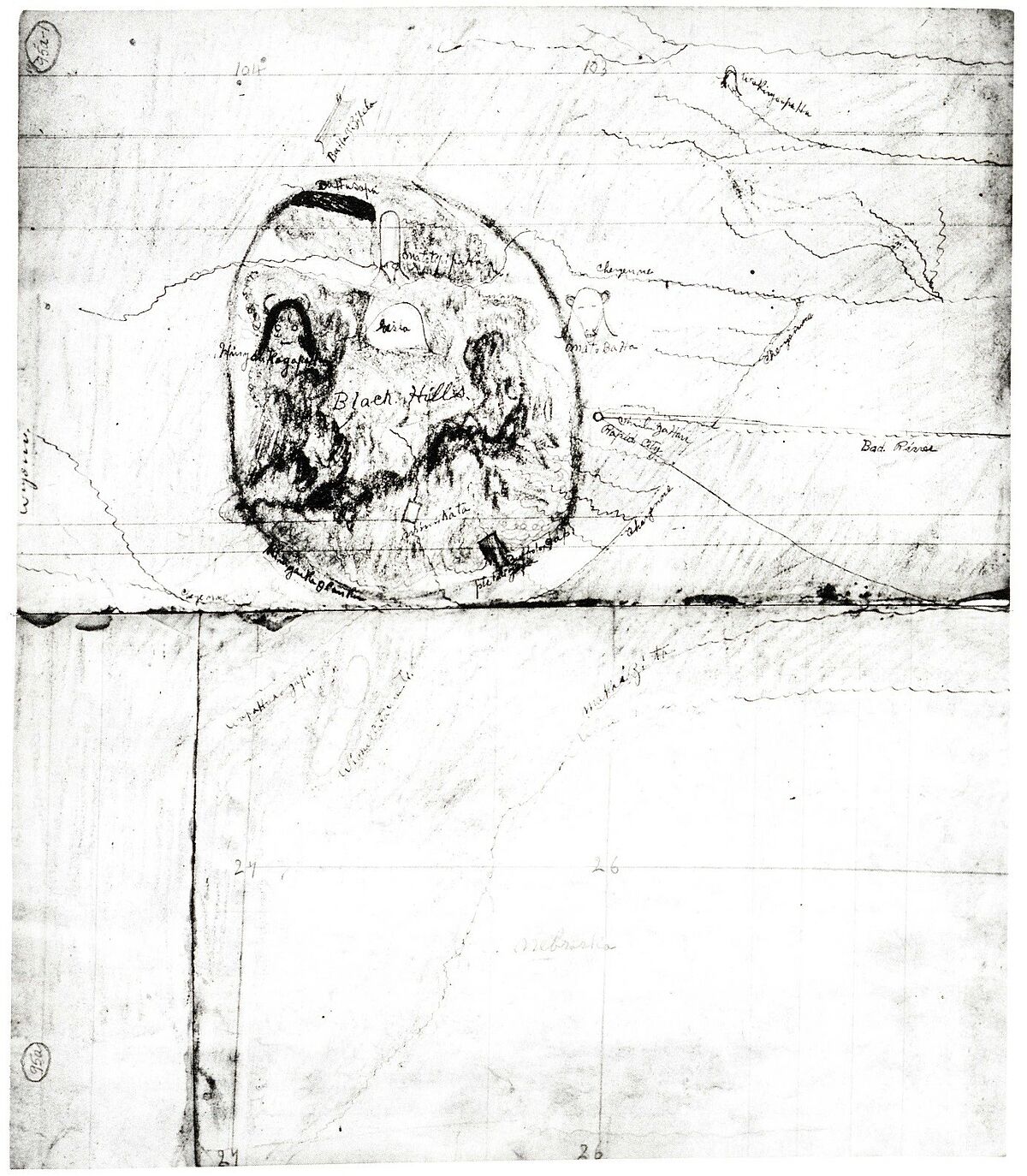

The Black Hills of southwestern South Dakota and eastern Wyoming are a place of natural beauty, interesting geology, and great spiritual power, which has attracted various groups of people throughout the ages. According to geologists, the complex story of the oval mountain range began more than two billion years ago and includes periods of uplift, volcanism and erosion (Raventon, 7-17). Oral traditions of the Lakota, Cheyenne, Arapahoe, Kiowa, Mandan, and other tribes speak of the great age of the Black Hills and the huge animals that once lived there. Lakota storyteller James LaPointe describes how “[f]ar back in the first sunrise of time (so say the legends), all the animals of the earth gathered here in the Black Hills for a big race” (17). He explains that the race was held to sort the animals into species and to determine their fate. At the end of the race, during which the animals circuited the Black Hills until gave up due to exhaustion, oval racetrack was carved deeply into the rock, leaving a bulging mound in its center – Paha Sapa, as the Lakota call the Black Hills. The Racetrack, stained by the blood of the defeated animals, is still visible today as Red Valley. Many sites inside and close to the Racetrack are special to the Lakota and other tribes, as illustrated by the famous Amos Bad Heart Bull map.

Bear Butte is located northeast of the Black Hills and is associated with artifacts and oral traditions that date human settlement there back several thousand years. Geologically speaking a laccolith (like the nearby Devils Tower), Bear Butte is a central place in oral traditions of various Native American tribes of the Plains, who have settled or traveled to the mountain at some point in their past.

Oral traditions of the Mandan and the Crow (Apsáalooke) tribes tell how the creation of the world took place at Bear Butte after a great flood. One of the earliest recorded versions of this story goes back to Reverend Peter Rosen, a European missionary who arrived in the Black Hills in 1882. In his Pa-Ha-Sa-Pah, Or the Black Hills of South Dakota (1895) Rosen quotes a creation story of the Crow tribes as follows:

“Long ago there was a great flood and only one man was left, whom we call the ‘Old Man,’ because it happened so long ago and we have talked of him so much. This ‘Old Man’ was a god. He saw a duck and said to it: ‘Come here, my brother.’ He was sitting on a high hill — Bear Butte.” (Rosen, 4)

The duck then dived to the bottom of the water and brought a piece of mud to the surface, which Old Man used to create the surrounding land and all living things. Rosen also refers to a tradition of the Mandan tribe, according to which Bear Butte is the site of an annual ceremony to honor Nu-mahk-muck-a-nah, the only man who survived a great flood by landing his canoe at the summit of Bear Butte (54).

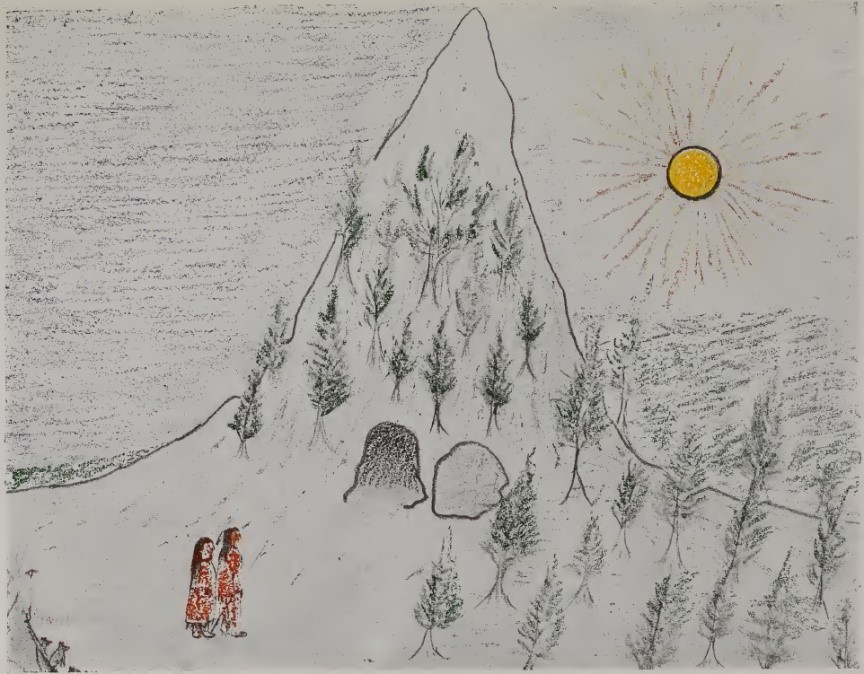

For the Cheyenne tribes – the Northern Cheyenne (Suhtai) and the Southern Cheyenne (Tsitsistas) – Bear Butte (Nowah’wus) is the most sacred place. They worship the landmark “as Sacred Mountain Where People Are Taught, or Medicine Pipe Mountain” (Sundstrom, 200). It is also the location where the creator bestowed the medicine arrows upon the famous Cheyenne hero Sweet Medicine. Sweet Medicine, prophet of the Tsitsistas, taught his people the proper way of life, ceremonies, and laws (Fixico, 190). Another story illustrates the origin of the Sundance ceremony and the deeds of Suhtai prophet Erect Horns. In the version recorded by American ethnographer George A. Dorsey, a medicine man takes the chief’s wife to Bear Butte to perform a ceremony that would bring back the buffalo and put an end to the famine that starves the tribe.

“Again they journeyed for several days, until they saw before them a forest, from whose midst there arose a mountain to the sky; beyond they saw great waters. […] On a beautiful morning they came to a large rock in front of the mountain. They rolled the rock aside, and found a passage, which they entered. When they had entered the rock rolled back in its place and closed them in. They were in the great lodge of the mountain. […] There the medicine-man and the woman received ceremonial instruction from the great Medicine, and from the Roaring Thunder, who talked to them from out the top of the mountain peak.” (Dorsey, 47-48)

At Bear Butte the great Medicine presented the medicine man with a horned cap, which – in combination with a ceremonial dance – enabled him to control the buffalo and other animals. Wearing the horned cap, the medicine man brought the buffalo back to his tribe and received the name Erect Horns, “for when he wore the cap the horns stood erect” (Dorsey, 48). Thus, Erect Horns brought the Cheyenne tribes ceremonial songs and the Sun Dance.

As mentioned before, Bear Butte is also a sacred landmark for the Lakota tribes. Many of their traditional stories related to the place describe how the mountain was created and why it received the name ‘Bear Butte’ (Mato Paha). According to one story presented by the Federal Writers Project – a project funded by the federal government during the Great Depression to provide jobs for out-of-work writers – Bear Butte was named after a vision of Crazy Horse’s father. In this vision, the Great Spirit appeared to the father in the shape of a bear granting him enormous powers. Being of old age, the father passed these powers on to his son Crazy Horse, who used them to fight the white people invading the Lakota tribes’ traditional land. Another story, recorded by Lakota storyteller James LaPointe, talks about a violent battle in ancient times.

“Thus one day in that ancient era of savage animals, a huge bear and an Unkche Ghila […] met in mortal combat. […] Finally, with a squeal of exhaustion and pain, the bear was forced to retreat. […] As the beaten animal sat in a weary slump, strange things happened. The earth trembled. Fire belched from its bowels and ashes rushed down with devastating force. Water and mud spouted skyward, plunging the earth in darkness and chaos. And then, as swiftly as it came, the havoc ended and there was calm. The air cleared. Instead of the pouting bear, there was a sharp mound, high in the air, still smoldering.” (LaPointe, 38)

The story acknowledges the peculiar shape, the violent events of the past, and the great age of Bear Butte. Storing the secrets of ancient events and prompting more recent mythologizing explanations of its shape, the mountain became a place of spiritual significance and the main site for the Hanblecheya (‘crying for a vision’) quest of the Lakota people. Up to this very day, members of the Lakota and other tribes go on pilgrimages to the sacred landmark. Yet, ever since European-American explorers and settlers became attracted to the unique setting of Bear Butte, conflicts over the sacred mountain ensued.

A Contested Sacred Place

In one of her essays about the sacred geography of the Black Hills, anthropologist Linea Sundstrom states that “[s]ome researchers assert that the concept of the sacred Black Hills is little more than a twentieth century scheme to promote tourism or part of a legal strategy to gain the return of Black Hills lands to Lakota and Cheyenne tribal governments” (185). She traces back this false assumption to the nineteenth century journals The Black Hills (1875) by Richard I. Dodge and Five Indian Tribes of the Upper Missouri (first published in 1930) by Edwin Denig. The two texts are among the first publications that gave rise to the narrative that the local tribes avoided Bear Butte for ‘superstitious’ reasons or due to the lack of animals and food (Sundstrom, 185/186). There are similar narratives for sacred places like Crater Lake, where European-American agents such as William Gladstone Steel, creator of Crater Lake National Park, contributed to the misconception that “[p]revious to 1886 no modern Indian ever looked upon Crater Lake” (Steel, 41). In both cases, the story of the landmark alleging that it just became sacred to the tribes after white people had put claims to it are blatantly wrong. There is plenty of evidence for the ancient sacredness of Bear Butte, and plenty of reasons why European-Americans have ignored this evidence.

Native American ‘landmark stories’, such as the examples mentioned above, give proof of the long history of indigenous settlement near Bear Butte. Additionally, finds of artifacts near Bear Butte date as far back as 10,000 years ago (Winter). The first European-American to lay eyes on the lonely landmark was probably the French fur trader Pierre de la Verendrye, who traveled through the region in the early 1740s (Rambow, 6). For the most part, Verendrye and other fur traders coexisted peacefully with the local tribes. This changed drastically when the American westward expansion and the gold rush in California drew settlers to the American West. In 1856, the most recent of the Lakota nation’s large congregations was held at Bear Butte to discuss how to deal with the settlers’ invasion of tribal land (LaPointe, 42). Eventually, the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie granted the Lakota, Dakota, and Arapahoe a large reservation which also included the land of the Black Hills. Yet only seven years later an expedition led by the infamous George Armstrong Custer set up their camp at Bear Butte and confirmed the rumors of gold in the area. The gold finds attracted large groups of settlers and caused numerous treaty violations, which resulted in battles between indigenous tribes and the United States Army. Although the Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapahoe famously defeated Custer and his men at the Battle of Little Bighorn in 1876, they were forced to cede the Black Hills just one year later. The sacred land of the Black Hills and Bear Butte were taken from the tribes, and the land’s very sacredness was soon ignored and denied by historians. Bear Butte was turned into a state park in 1961 and the surrounding land was made open to the public as campground and recreation area. In 1981, Bear Butte became a National Historic Landmark.

Forcefully and unjustly detached from their traditional lands, the Lakota, Cheyennes, and other tribes struggled for survival and the preservation of their cultural beliefs. During times of assimilationist policies, tribal members, such as the famous Lakotas Black Elk and Luther Standing Bear and the Dakota scholar Charles Eastman recorded cultural practices, religious beliefs, and historical events. However, major movements for tribal independence formed especially after World War II. Charles Rambow describes how a movement led by Lakota leader Frank Fools Crow revived practices such as the Hanblecheya and that “Bear Butte Mountain and the Sun Dance were two of the strongest symbols to keep the spiritual surge alive” (Preface, v). After the American Indian Religious Freedom Act was enacted in 1978, ceremonial use of Bear Butte as sacred place increased significantly. But with the revival of indigenous use of Bear Butte the conflict about who may claim the mountain rose yet again. In the famous case Frank Fools Crow et al. v. Tony Gullet et al. (1982) Oglala Lakota leader Frank Fools Crow and other plaintiffs argued for the protection of the tribes’ religious rights based on the First Amendment, the American Indian Religious Freedom Act of 1978, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. The courts ruled against the tribal claims and the applicability of the First Amendment arguing that compelling state interest in promoting tourism and recreation overrode Indigenous religious rights.

Historians like Watson Parker and Donald Worster were convinced that the Black Hills “area was not viewed as holy ground prior to the 1970s” (Sundstrom, 185). With the historical events just mentioned in mind, this claim is ill-informed and cynical. Having struggled for decades and centuries to protect their traditional lands, the Lakota and other tribes of the area still have to fight for their traditional rights up to this day. Most recently, the annual Sturgis Motorcycle Rally caused disputes between tribal members and other citizens of the area. Entrepreneurs had plans for a biker bar (called the Full Throttle Saloon) with a stage for live music and campgrounds no more than two and a half miles distant from Bear Butte (Robbins). The bar was built despite massive protests of the local tribes, but burned down in 2015. Currently, the owners of the Full Throttle Saloon are rebuilding the bar at a different location even closer to Bear Butte. Lakota protesters fear that this construction could trigger further development of the area, and are determined to protect the sacredness of Bear Butte.

What Does the Past Mean for the Present?

Native American tribes have inscribed the landscape of Bear Butte and the Black Hills for millennia. Despite material and oral evidence, and treaty claims for the area, tribal influence on the fate of the sacred mountain is limited. Tourists hike up the mountain, the noise of biker bars and the annual motorcycle rally disturb the tranquility of the place, and some historians question the ancient tribal affiliation to Bear Butte – which is most prominently documented in the movie Powwow Highway (1989) starring A Martinez, Gary Farmer, and Amanda Wyss, where the protagonists pay their reverence to the spirit powers by placing a Hershey’s bar at the rock. Up to this day visitors of the site will find prayer cloths and bundles hanging from trees, tribal members going on their Hanblecheya and other quests, and members of various local tribes protesting against development and nuisance businesses near Bear Butte. Although the landmark has been re-inscribed many times throughout history, it maintained its spiritual power to unite members of Native American tribes and provide them with visions.

Bear Butte is a special landmark because it tells stories of time immemorial, stories of colonial violence, and stories of tribal resilience. Its embattled status between spiritual interests of various tribes and economic interests of American leisure society is indicative of other legal battles over sacred places. As such, the site has been a place of contact and battle ever since the fight between the giant bear and the Unkche Ghila. Testifying to the spiritual importance and the ancient memories of their land, the ‘landmark stories’ of the Lakota, Cheyenne, and others remind us of America’s deep past. In this context, landmarks like Bear Butte are of immeasurable value as places of memory.

WORKS CITED

Bad Heart Bull, Amos, and Helen H. Blish. A Pictographic History of the Oglala Sioux. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1967.

Brown, Brian E. Religion, Law, and the Land: Native Americans and the Judicial Interpretation of Sacred Land. Contributions to Legal Studies. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1999.

Dorsey, George A. The Cheyenne. I. Ceremonial Organization. Chicago: Field Columbian Museum, 1905.

Federal Writers Project. Legends of the Mighty Sioux. New York: AMS Press, 1941.

Fixico, Donald L. "That's What They Used to Say": Reflections on American Indian Oral Traditions. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2017.

LaPointe, James. Legends of the Lakota. San Francisco: The Indian Historian Press, 1976.

Rambow, Charles. Bear Butte. Journeys to the Sacred Mountain. Sioux Falls: Pine Hill Press, 2004.

Raventon, Edward. Island in the Plains: A Black Hills Natural History. A Black Hills Natural History. Boulder: Johnson Books, 1994.

Robbins, Jim. “For Sacred Indian Site, New Neighbors Are Far From Welcome.” New York Times. 4 Aug. 2006. Access 20 April 2018.

Rosen, Peter. Pa-Ha-Sa-Pah, Or the Black Hills of South Dakota. St. Louis: Nixon-Jones Printing Co., 1895.

Steel, William Gladstone. “Crater Lake.” Steel Points 1, 2 (1907).

Sundstrom, Linea. “The Sacred Black Hills. An Ethnohistorical Review.” Great Plains Quarterly 17 3/4 (1997) 185-212.

Winter, Karly C. “Saving Bear Butte and Other Sacred Sites.” Great Plains Natural Resources Journal 13, 1 (2010) 71-84.

FURTHER READING

Ostler, Jeffrey. The Lakotas and the Black Hills. The Struggle for Sacred Ground. New York: Viking, 2010.

ILLUSTRATIONS

Figure 1: Jerrye & Roy Klotz MD. BEAR BUTTE. 2007. Wikimedia Commons. Wikimedia Foundation. Web. 23 April 2018. commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:BEAR_BUTTE.jpg.

Figure 2: Bad Heart Bull, Amos. No. 198. Early Social Life and Reorganization. 1890-1913. A Pictographic History of the Oglala Sioux. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1967. 289.

Figure 3: Richard Davis et al. They Discover the Sacred Mountain. 1901-1905. The Cheyenne. I. Ceremonial Organization. Chicago: Field Columbian Museum, 1905. Plate 14.