From Prehistory to Deep History: The Coloniality of Counting Time

by Stefan Krause, 06/10/2016.

Summary

What do we mean when we call something ‘prehistoric’? Does the term refer to times or people without a writing system? Does it imply that cultures before the beginning of history are inferior? Or does it simply describe a very early stage of human development, or even a period before the appearance of man on earth? Over the past decades the division into ‘prehistory’ and history proper has kindled heated academic debates. Some scholars see ‘prehistory’ as stigmatizing certain cultures as ‘people without history’ and argue that the concept of history needs to be revised. This article seeks to outline the origin and growing criticism of this debate. It also discusses alternatives such as the concept of ‘deep history’ and how these alternatives can improve our understanding of America’s past in particular, and mankind’s past in general.

The study of the human past is a multidisciplinary project. The spatial and temporal focus areas of scholars of the past depend on their academic background. For example, biological anthropologists analyze the biology and evolution of humans, which can be dated back as far as 7 million years ago.[1] Archaeology examines human remains and material culture with artifacts as old as 2.6 million years.[2] Historians generally study written records of the human past, the oldest of which might have been produced in ancient Mesopotamia some 5,000 years ago. It is obvious that these approaches to mankind’s past differ significantly regarding the period they study. The most important and controversially discussed distinction is the one between ‘history’ and ‘prehistory’. Traditional definitions lead back to Hegel’s Lectures on the Philosophy of World History in the 1820s, in which he excluded India, China, and Africa from the successive unfolding of the human spirit toward freedom because he regarded these societies as static and without a knowable past. For Hegel, the term ‘history’ covers those periods of the human past for which we have written records while human societies without written scripts and non-textual material finds belong to the realm of the prehistorical. For the past few decades, the Hegelian distinction between history and non-history or prehistory has received a lot of criticism from third world and postcolonial scholars.

The Origins of ‘Prehistory’

Ever after Hegel’s influential distinction, ‘prehistory’ has come to refer to those aspects of the past that can only be reconstructed on the basis of archaeological and material evidence. It differs from the field of ‘history’ in crucial methodological ways. Put simply: the historian reads, the archaeologist digs. History is the older of the two fields and has been practiced ever since Herodotus and Thucydides some 400 years BCE. The concept of a “prehistoric period” (période anti-historique) is rather recent and has been coined by the French archaeologist Paul Tournal in 1833 (Fagan 4). A few years later, the Scottish-Canadian scholar Daniel Wilson introduced the term ‘prehistoric’ into the English language in his The Archaeology and Prehistoric Annals of Scotland (1851).[3]Historian Donald R. Kelley attributes the rising interest in the material culture of ‘prehistorical’ societies to the emerging sciences of anthropology and archaeology (22). Yet it is also possible that these sciences simply fulfilled a growing desire to know about the distant past – a desire usually associated with the rise of national states. One of the most comprehensive books about modern societies’ manufacturing of a useable past is David Lowenthal’s The Past is a Foreign Country (1985). Lowenthal examines how the past, constantly reconstructed but also reinvented, can be both comforting and a burden, how collective memory and heritage are an integral part of our identity.

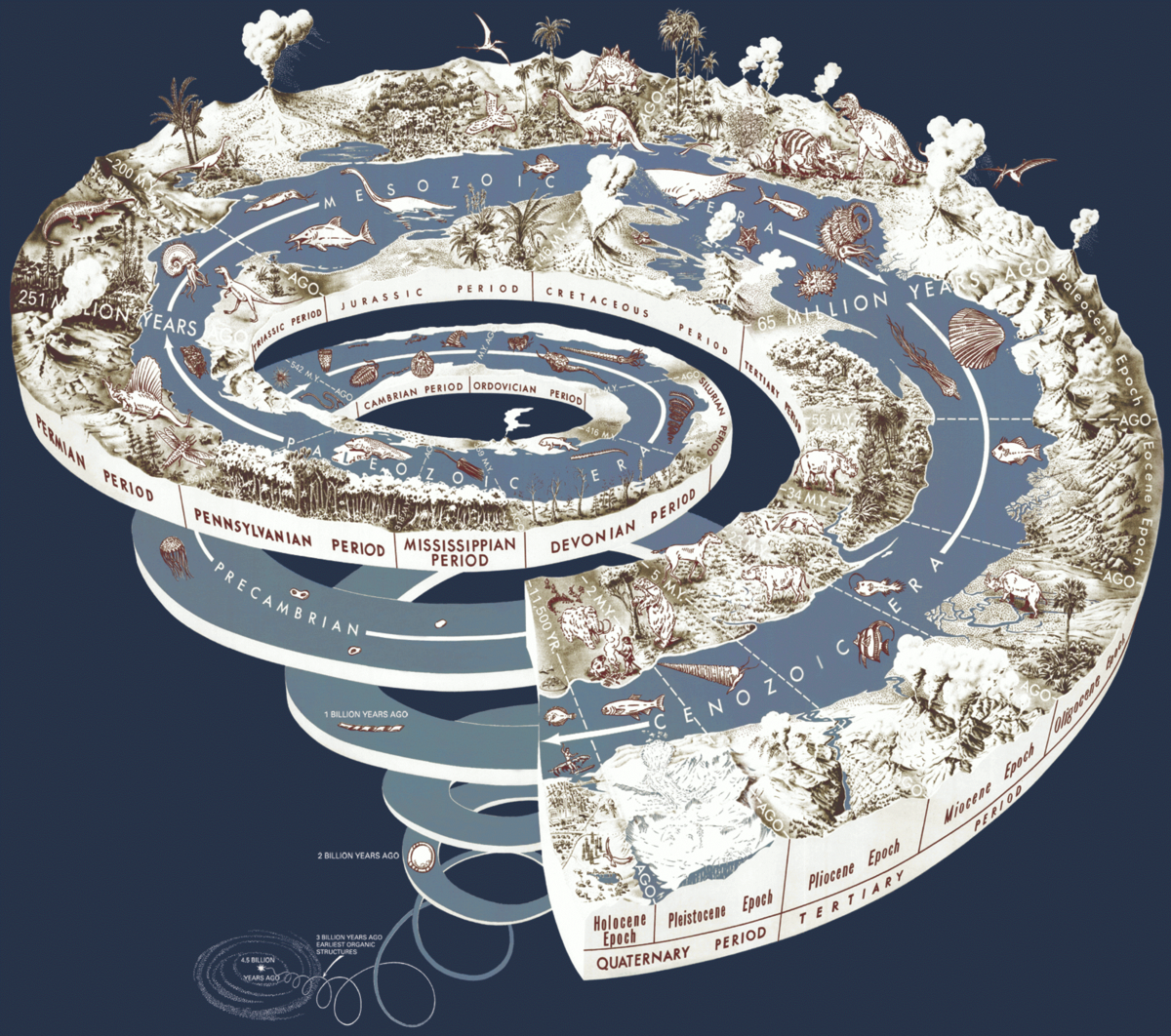

The growing fascination with the antiquity of man was motivated by two major developments. First, the discovery and research of deep time (geological time) by geologists such as James Hutton and Charles Lyell who revised inherited understandings of temporal order. Up to the middle of the nineteenth century most scientists based their works on the biblical dogma formulated by Bishop James Ussher in 1650, according to which the earth was created on Tuesday, October 23, 4004 BCE, at 9:30 in the morning. At the end of the eighteenth century, Hutton studied the structure of soil and rocks and concluded that the earth had been shaped by incredibly slow and perpetual processes (uniformitarianism) – an observation on which Charles Lyell later elaborated in his opus magnum Principles of Geology (1830-33). Their empirical findings suggested that the earth was ancient and that its past was too vast to be compatible with Ussher’s calculation. In his book Time’s Arrow, Time’s Cycle (1987) Stephen J. Gould argues that the writings of Hutton and Lyell have often been misrepresented. Gould shows that their work was based on both a linear and cyclical concept of time and presents a case study of how culture and religion influence scientific discoveries. Finally, Charles Darwin’s evolutionary theory, developed in On the Origin of Species (1859), forced scientists to accept that the antiquity of man and other species by far surpassed the biblical time count. While Lyell’s and Darwin’s discoveries led to a significant religious crisis, the scholarly interest in ancient human societies and their origin increased and, starting in the second half of the nineteenth century, gave birth to new scientific disciplines such as paleoanthropology and prehistoric archaeology.[4]

A second and sometimes related aspect were political interests of Western colonial governments. Labeling human societies as prehistoric – or as seemingly unchanged remnants of ancient times – helped to enforce certain colonial policies.[5] In the United States, the American government reinforced their claim to land in the west after the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. However, there were people living on this land: the indigenous people of America. For many prospective settlers the region west of the Mississippi River was still a wild and uncharted land, and they wanted to know more about the dangers and treasures of the west. Fossil hunters and amateur archaeologists like Albert C. Koch dug up bones of ancient creatures such as Mastodons in the western wilderness and displayed them in their museums, which inspired fantasies of a prehistoric west inhabited by ‘savage’ tribes and primeval giants. Other scholars studied the mounds of the Mississippi valley and elsewhere, assuming they had been erected by cultures that had long since disappeared. Archaeologists did not acknowledge contemporary Native Americans’ affiliation with the Mound Builders until the second half of the nineteenth century. Instead, indigenous tribes were systematically illustrated as primitive people stuck in an earlier stage of human history. This depiction of Native Americans as uncivilized and ‘prehistoric’ people helped to justify the removal and territorial dispossession of Indian tribes. Those who had not climbed up the ladder of civilization (promoted by early anthropologists such as Edward B. Tylor and Lewis H. Morgan) were seen to belong to a lower or earlier stage of human development and to be unfit to meet the challenges of the modern age. The notion that ‘civilized’ people replaced the ‘uncultured’ population was a widely accepted pattern of man’s history. Thus, one could argue, the westward expansion not only dispossessed the indigenous inhabitants, but ideologically transformed the American West from a land of ‘prehistory’ into a land of ‘history’.

The Keepers of Time and Makers of (Pre)History

Scholars like anthropologist Alice Beck Kehoe discuss the term ‘prehistory’ in the context of the history of American archaeology. According to Kehoe, American archaeology has, from its beginnings up to the second half of the twentieth century, been “a profession visibly nearly exclusively white, male, Protestant, and American born” (Introduction, xiv), and the concept and study of prehistory has thus been politically and ideologically governed by a specific group of people.[6] Therefore, it seems that ‘prehistory’ has excluded people both on a temporal and academic basis. Anthropologist Johannes Fabian formulated similar thoughts for the history of anthropology. In Time and the Other (1983) he examines how social/cultural evolutionist thinkers like Edward Burnett Tylor, Lewis Henry Morgan, and Herbert Spencer adapted ‘naturalized Time’ (i.e. geological/deep time) into early anthropological discourse to support their cultural evolutionist arguments, which Fabian criticizes as “sadly regressive intellectually, and quite reactionary politically” (16). Fabian illustrates that the result was an allegedly science-based narrative of mankind’s past that was used to place contemporary societies within different evolutionary stages. Others argue along similar lines with regard to the study of history. In his book, Europe and the People Without History (1982) anthropologist Eric Wolf focused on the spatial outline of history and criticized the Eurocentric concept of history as exclusive and insufficient. Wolf argued for a ‘history’ that includes non-Western agents such as “‘primitives’, peasantries, laborers, immigrants, and besieged minorities” (Preface 1982, xxvi). With the critique by writers like Kehoe and Wolf, the call for a more inclusive approach to time and history became louder.

The Depth of Time and the Human Past

The different time frames within which scientists study mankind’s development always focus on one area of the past while neglecting others. Although this specialization is necessary, a more connected narrative of humanity’s past seems possible. In the first years of the twenty-first century and under the impact of postcolonial approaches, scholars have started to revise the structure of mankind’s past. Historians such as Lynn Hunt and Daniel Lord Smail have proposed new ways to structure and measure history.

In Measuring Time, Making History (2008) Hunt writes about how Western dating systems and concepts like ‘modernity’ have shaped and dominated our understanding of history. She critically reflects the limitations and biases of history and calls for a non-teleological, secular, and deep-time approach toward the past (108). Hunt wants to free history from the Eurocentric temporal and spatial boundaries, which have created teleological categories such as ‘ancient’, ‘medieval’, and ‘modern’ and cover only the Western narrative of the past. In this context, she also refers to scholars like Sanjay Subrahmanyam and Smail, who support a concept of ‘history’ that includes Paleolithic people and does not dismiss ‘ancient’ and indeed non-European cultures as ‘prehistoric’.

Smail is one of the most prominent proponents of deep time in history. In their book Deep History (2011) Smail, anthropologist Andrew Shryock, and others try to link humanity’s past to its natural history (i.e. human evolution). They acknowledge that thanks to “archaeologists and paleoanthropologists, prehistory today is carefully mapped, meticulously dated, and creatively analyzed” (Preface, x). Considering this available knowledge, Shryock and Smail suggest that the study of mankind’s history should no longer exclude times and cultures on the basis of their different historicality. Their goal is to enlarge the scale of humanity’s story by making the process of writing this story an interdisciplinary one.[7] Although their concept of deep history has overcome the controversial dichotomy of history and prehistory, Smail and his colleagues may have to face the criticism of being too ambitious in their goals and of neglecting some non-Western approaches to the past (e.g. oral traditions). This gap is mended by the essays in the collection The Death of Prehistory, edited by Peter Schmidt and Stephen Mrozowski, who speak of the “tyranny of prehistory” and who emphasize non-Western ways of recording history and maintaining an historical consciousness.

One of the latest developments, “big history,” expands the temporal scope much further, covering the timespan from the big bang up to the present day.[8] As such, big history combines cosmology, archaeology, history, and astronomy, amongst others, exploring the ultimate depths of the past.

Depth and Breadth of America’s History

Debates about the scale and role of history are important issues for our work. Our project focuses on the construction of America’s distant past; a theoretical framework that provides the means to structure and study this past is an essential part of this venture. It is our goal to examine how America’s past has been studied, who the agents of this scholarly discourse were (see section on “Agents”), and which knowledges of America’s past do exist. In this endeavor we follow the theoretical groundwork of Wolf, Gould, Fabian, Hunt, and Smail and attempt to analyze various discourses on American antiquity that challenge categories such as ‘ancient’, ‘prehistoric’, ‘modern’, and ‘historic’. We believe that by deepening and widening the scale of history it is possible to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the past and thus a better foundation for building a common future.

Many of the articles on this website focus on specific cases that illustrate the chances arising from a temporally, spatially, and culturally enlarged scale of the past. Stories like “Chachapoyas”, “Pleistocene Overkill” or the debate about the provenance of the “Kennewick Man” show how Western constructions of the past may produce distorted images of America’s distant history and how these distortions influence political debates (e.g. over land, hunting rights, fishing rights, etc.) up to this day. The granting of the right of ‘historicality’[9] to people of all cultures, whether they use literate or oral or other communication media, can be helpful in creating a space in which knowledge of the past becomes a collaborative cross-cultural project.

NOTES

[1] If we accept Sahelanthropus tchadensis as one of the earliest hominins, we can trace the past of this taxonomical tribe back to roughly 7 Mya. Alternatively, Orrorin tugenensis (ca. 6 Mya) or Ardipithecus spp. (ca. 5.5-4.5 Mya) can be considered the earliest known hominins.

[2] Recent finds of stone tools at Lomekwi, Kenya, could be as old as 3.3 Mya.

[3] Alice Beck Kehoe discusses Daniel Wilson’s role in the construction of prehistory in her book The Land of Prehistory (1998).

[4] The classical study of this scientific discovery of modern time is Stephen Jay Gould, Time’s Arrow Time’s Cycle (1987).

[5] In The Land of Prehistory Kehoe discusses how American archaeology “has been politically charged, legitimating domination of North America by capitalists imbued with British bourgeois culture” (Introduction, xi).

[6] It is important to mention that this has changed significantly since the end of the twentieth century.

[7] Their team of authors includes historians, archaeologists, cultural anthropologists, a linguist, a primatologist, and a geneticist (Smail & Shryock, 18).

[8] For an introduction to ‘big history’ see historian David Christian’s Maps of Time (2005).

[9] Hunt defines “historicality“ as “the definition of what constitutes the historical” (124). Postcolonial writings like Dipesh Chakrabarty’s Provincializing Europe (2000), as well as texts by classic historians of orality and literacy such as Jack Goody’s The Theft of History (2006), are demanding that historicality be extended to cultures outside of the occidental West. See also Gesa Mackenthun, “Night of First Ages.”

WORKS CITED

Chakrabarty, Dipesh. Provincializing Europe. Postcolonial Thought and Historical Difference. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2nd. ed. 2008 (2000).

Christian, David. Maps of Time: An Introduction to Big History. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004.

Fabian, Johannes. Time and the Other. How Anthropology Makes its Object. New York: Columbia University Press, 1983/2002.

Fagan, Brian M. People of the Earth: An Introduction to World Prehistory. 13th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall/Pearson, 2010.

Goody, Jack. The Theft of History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

Gould, Stephen Jay. Time’s Arrow Time’s Cycle. Myth and Metaphor in the Discovery of Geological Time. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1987.

Hunt, Lynn. Measuring Time, Making History. Budapest, New York: Central European University Press, 2008.

Kehoe, Alice B. The Land of Prehistory: A Critical History of American Archaeology. New York: Routledge, 1998.

Lowenthal, David. The Past is a Foreign Country. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985. New edition 2015.

Mackenthun, Gesa. “Night of First Ages: Deep Time and the Colonial Denial of Temporal Coevalness.” Crossroads in American Studies: Transnational and Biocultural Encounters. Ed. Frederike Offizier, Marc Priewe, Ariane Schröder. Heidelberg: Winter, 2016. 177-213.

Schmidt, Peter R., and Stephen A. Mrozowski, eds. The Death of Prehistory. Oxford University Press, 2013.

Shryock, Andrew & Daniel L. Smail. Deep History: The Architecture of Past and Present. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011.

Wolf, Eric R. Europe and the People without History. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1982.