Albert C. Koch

by Gesa Mackenthun, 03/04/2016.

Summary

Albert C. Koch, a German immigrant from Saxony, ran a museum with American archaeological antiquities in St. Louis, the gateway to the West, in the 1830s and 1840s. The museum served to procure the money Koch needed for excavating fossil skeletons of extinct animals in North America. In 1840, Koch discovered the complete skeleton of a mastodon which he dubbed “missourium.” He generously added a few vertebrae from other animals when he recomposed his creature and exhibited it in his museum before taking it on tour to the East Coast and Europe. The ‘fraud’, which Koch committed in later cases as well, was quickly discovered and severely criticized by scientists on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean. This has obscured the fact that Koch was the first to pronounce the contemporaneity of the mastodon and human beings in America – a theory that was hard to stomach for science in general and for colonial science in particular.

On 24 March, 1840, Albert C. Koch learned of the discovery of the skeleton of a gigantic beast on the grounds of a farmer in Benton County, near Kimmswick, Missouri.

Although Koch was ill with a fever, he decided to hurry to the site and supervise the excavation. He took a steamboat on the Mississippi from St. Louis, where he ran a museum of Indian artifacts and fossil bones. After six days and an arduous march through virgin forest he reached the spot near the confluence of the Pomme de Terre River and the Osage River. His sacrifice was rewarded: after 4 months of digging with different teams, Koch and his workers unearthed the skeleton of an extinct creature which he named Missourium (or sometimes Missouri Leviathan or Mastodon giganteus) (Stadler xxiv-xxv). He proudly took it home to St. Louis where he had the skeleton rebuilt and exhibited for the public whom he invited with the alluring slogan “Citizens of Missouri, come and see the gigantic race that once inhabited the space you now occupy, drank of the same waters which now quench your thirst, ate the fruits of the same soil that now yields so abundantly to your labor” (quoted in Stadler xxv).

An Immigrant Impresario

Koch was an immigrant from Germany. He had been born in Roitzsch near Dresden in Saxony in 1804 and emigrated to America in 1826. According to the historical archives he makes his next appearance in St. Louis where he opened a museum whose exhibitions and “vaudevillelike” shows of dead and living curiosities he used to raise the money for pursuing his real passion: the excavation and interpretation of fossil remains, as well as the collection of artifacts from Native Americans. Koch is frequently compared with P.T. Barnum who used his American Museum in New York for similar purposes. Both inhabited the grey area between serious science on the one hand and the entertainment industry on the other – frequently necessary to finance the scientific pursuits in absence of sponsors. “Although accounts of exhibitions at his museum tended to relate the spectacular and the bizarre,” McMillan concludes, “the museum did contain a number of important natural history collections that provided substance for inquiry by scholars of the time.” It harbored a large collection of indigenous artifacts given to Koch by William Clark, and Koch’s many fossils of extinct animals did attract the curiosity of pleasure-seekers and scientific personalities alike.

Addressing the non-scientific public, Koch’s announcement of the “gigantic race” intelligently uses his visitors’ preoccupation with the lands west of St. Louis where many of them were seeking to start a new life while it also appealed to their latent fears of the unknown areas in the West. After all, only a few decades earlier, in his Notes On the State of Virginia (1781), Thomas Jefferson had speculated on the possibility that live mammoths might yet roam freely in the unexplored regions west of the Mississippi![1] Yet as “gigantic” as it was, this fossil “race” was less to be feared than the members of the human “race” who still roamed the prairies, ready to fight for the preservation of their way of life.

The enthusiastic reaction to the exhibition of the “missourium” motivated Koch to shut down his museum in 1841 and to go on tour with his fossils. He showed his treasure in New Orleans, Philadelphia, then across the Atlantic in London and Dublin and finally in his country of origin.

Scientists soon realized that Koch had taken his liberties in arranging the skeleton of his prehistoric monster, enlarging it significantly by adding a few bones from other fossils.

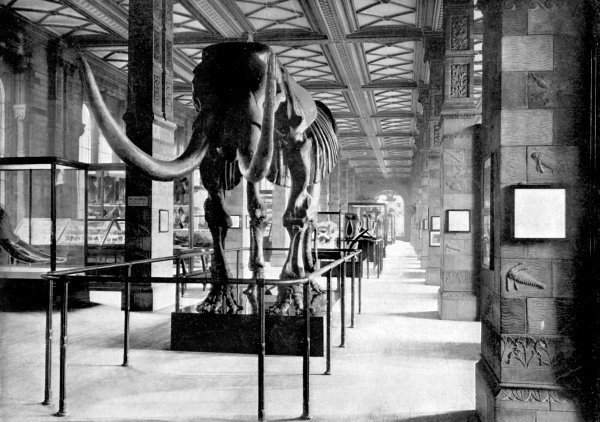

In spite of this critique, by Richard Owens and others, the British Museum in London bought the “missourium” for 1,300 pounds. Its curators corrected the structure and identified the animal as a regular American mastodon. The “missourium” is still in the possession of the Natural History Museum in London.

Koch discovers Moby Dick's Ancestor

Having left many of his fossil bones with the Royal Museum in Berlin, Koch returned to America and traveled the country for two years in search of further fossils, in particular of a visionary sea serpent – which he finally found in Alabama in 1845 (Stadler xxviii-xxix). He baptized the 114 feet-long skeleton “Hydrarchos,” showed it on Broadway in New York and claimed that is was the largest fossil skeleton ever found. In the pamphlet that accompanied his exhibition he links the creature to the biblical accounts of Leviathan from the Book of Job – an association that may have inspired Herman Melville’s half-horrified, half-satirical account of the “fossil whale” in Moby-Dick (1851). Here is the New York Evangelist on Koch’s “Hydrarchos”: “who knows but he [Koch’s Leviathan] had seen the Ark? Who knows but Noah had seen him from the window? Who knows but he may have visited Ararat? […] Perhaps, when we now touch his ribs, we are touching the residium of some of Cain’s descendants, that perished in the deluge” (quoted in Stadler xxix-xxx). And here are some of Ishmael’s ruminations about the antiquity of the fossil whale, which make direct reference to the fossil finds in Alabama: “this Leviathan comes floundering down upon us from the head-waters of the Eternities. […] He swam the seas before the continents broke water; he once swam over the site of the Tuileries, and Windsor Castle, and the Kremlin. In Noah’s flood he despised Noah’s Ark; and if ever the world is to be again flooded, like the Netherlands, to kill off its rats, then the eternal whale will still survive.”[2]

Scientists who saw Koch’s “Hydrarchos” soon realized that this skeleton, too, consisted of parts from several individuals and different kinds of animals (variously called Zeuglodon and Basilosaurus) and that, as before, its size was the result of artificial elaboration. Koch nevertheless showed “Hydrarchos” in Dresden, at the 1847 Leipzig fair, and in Berlin. Here he was given a yearly lifetime pension by King Friedrich Wilhelm IV of Prussia which should have ended his financial strains. Koch returned to Alabama, unearthed another Zeuglodon, which he likewise shipped to Dresden, followed by a tour to Breslau, Vienna, and Prague (Stadler xxxi). In the mid-fifties, the “peripatetic paleontologist” (as Stadler dubs him) finally settled down in St. Louis where he co-edited a German-American merchant paper. In the 1860s he entered into the geological exploration of Tennessee for iron, lead, coal, and petroleum which led to the formation of the Knoxville Oil and Mining Company (Stadler xxxii). As before, Koch belonged to the avant-garde of new scientific developments – the study of fossils and the drilling for oil. He died in Golconda, Illinois, in 1867.

The Cultural and Scientific Significance of Albert Koch

The historical figure of Albert Koch condenses various aspects of our research project: First, he represents the transatlantic dimension of the discourse on antiquities. As in other cases, we can observe an intense transoceanic circulation of scientific ideas in the nineteenth century, which the immigrant Koch exemplifies. Secondly, he represents the frequent blending of scientific and popular practices. As other illustrious figures of his time, Koch combined scientific interest with a desire to exploit the potential of the growing amusement culture. Like his contemporary John Lloyd Stephens, Koch unites an interest in American antiquity with an interest in new technologies and industrial products. Third, the spatial site of Koch’s science fuses the hunt for the traces of antiquity with the geographical area of western expansion: stopping by Koch’s exhibition in St. Louis, many settlers might have regarded it as a gateway to unknown worlds and unexplored regions where the Frontier is not only the contact zone between immigrants and Native tribes but also between the present and the distant past – evoking Joseph Conrad’s imperial trope of unconquered areas as remaining locked in the “Night of First Ages.”[3]

Fourth, the reception of Koch’s exhibits and his ideas about them illustrates the fierce ideological battles within the emerging field of the earth sciences. While the critique of his erroneous construction of his skeletons is justified, another idea of his deserves serious consideration but was likewise rejected: Koch repeatedly mentioned the discovery of human artifacts (spears) in close vicinity, or even within, the mastodon skeletons, which convinced him that these monsters cannot have been antediluvian but must have coexisted with man – that in at least one case the animal had actually been killed by men (quote by Dana 338-40). Like Jefferson, Koch refers to Native American oral traditions as evidence of the coexistence of men and mastodons in America. Koch was the first so make such a claim for America.[4] The hypothesis of the coexistence of men and extinct animals was new at that time and still hard to swallow for many scientists who were seeking to reconcile their findings with the historical narrative of the Bible (i.e. that the world had only existed for 6,000 years). The British-American anthropologist M.F. Ashley Montagu wrote of Koch’s discovery in 1944: “In this, the earliest account of the association of human artifacts with the remains of fossil mammals in North America, we have, oddly enough, one of the clearest and best evidences of the antiquity of man in North America that has ever been published. Yet Koch’s statements have nearly always been dismissed as unworthy of belief. He has been ridiculed and completely shut out of court” (quoted in Stadler xxxiii). Probably the most dismissive comments on Koch’s scientific expertise come from Richard Dwight Dana, one of the United States’ most renowned geologists. In his essay “On Dr. Koch’s Evidence with regard to the Cotemporaneity of Man and the Mastodon in Missouri” (1875), Dana seems to belittle Koch’s geological expertise strategically in order to reject Koch’s assumption about the concurrence of mastodon (missourium) and man. To disprove this thesis seems to be the main goal of Dana’s essay (which begins and also ends with it). He arrives at the conclusion that the evidence of the contemporaneity is “very doubtful” (346). But surprisingly his essay ends with the words: “The cotemporaneity [sic] claimed will probably be shown to be true for North America by future discoveries if not already so established; for man existed in Europe long before the extinction of the American Mastodon” (346; emphasis added). Dana’s admission that man may have existed before the disappearance of extinct animals in America as well as in Europe comes as a surprise after his previous passionate rejection of Koch’s assertions to the same effect. We may here diagnose a textual slippage, indicative perhaps of a certain resentment against the foreign immigrant but more importantly of the larger ideological conflict of a settler nation which, in the 1870s when Dana was writing this, was violently displacing America’s ancient – but not extinct – human “race.”

NOTES

[1] Jefferson, Notes on the State of Virginia 43; 53-54.

[2] Melville, Moby-Dick 381; 385. See also see Dana’s summary of Koch’s arguments (Dana 336).

[3] See Mackenthun, “Night of First Ages“.

[4] On the history of this scientific insight in Europe see van Riper.

WORKS CITED

Buckley, S.B. “On the Zeuglodon Remains in Alabama.” American Journal of Science 52 (November 1846). 125-33. Online. http://books.google.de/books?id=xhEeAQAAMAAJ&pg=PA126&dq=Judge+Creagh&hl=de&sa=X&ei=eWTDT8SRJsbctAaEzJnlCg&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=Judge%20Creagh&f=false.

Dana, J.D. “On Dr. Koch’s Evidence with regard to the Contemporaneity of Man and the Mastodon in Missouri.” The American Journal of Science and Arts 9 (1875): 335-46. This is a collective review of six of Koch’s works. Contains lengthy quotations from both of Koch’s texts in which he argues the contemporaneity of mastodon and man in America. Online. https://books.google.de/books?id=aXgrAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA346&dq=J.D.+Dana+Koch%27s+Evidence&hl=de&sa=X&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=J.D.%20Dana%20Koch's%20Evidence&f=false.

Jefferson, Thomas. Notes on the State of Virginia. 1781. Ed. William Peden. Chapel Hill: North Carolina University Press, 1982.

Koch, Albert C. Description of the Missourium, or Missouri Leviathan. Louisville, KY: Prentice and Weissinger, 1841. Online. http://books.google.de/books?id=OccoAQAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=Albert+C.+Koch&hl=de&sa=X&ei=jmDDT4SaOInbsgbMh8zkCg&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=Indians&f=false.

Koch, Albert C. Die Riesenthiere der Urwelt; oder das neuentdeckte Missourium Theristocaulodon (Sichelzahn aus Missouri) und die Mastodontoiden. Berlin: Alexander Duncker, 1845. Online.

Koch, Albert C. Reise durch einen Theil der Vereinigten Staaten von Nordamerika in den Jahren 1844 bis 1846. Dresden: Arnold, 1847.

Koch, Albert C. Journey through a Part of the United States of North America in the Years 1844-1846. Reprint. Transl. & Intro. Ernst A. Stadler. Carbondale and Edwardsville: Southern Illinois University Press, 1972.

Mackenthun, Gesa. “Fossils and Immortality. Geological Time and Spiritual Crisis in Nineteenth-Century America.” Deutungsmacht.Religion und Belief Systems in Deutungsmachtkonflikten. Ed. Philipp Stoellger. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2014. 259-83.

Mackenthun, Gesa. “Night of First Ages: Deep Time and the Colonial Denial of Temporal Coevalness.” Crossroads in American Studies: Transnational and Biocultural Encounters. Ed. Frederike Offizier, Marc Priewe, Ariane Schröder. Heidelberg: Winter, 2016. In print.

McMillan, R. Bruce. “Objects of Curiosity. Albert Koch’s 1840 St. Louis Museum.” The Living Museum 42,2/3 (n.d.). Online. Largely reproduces Stadler. http://www.academia.edu/3584620/Objects_of_Curiosity_Albert_Kochs_1840_St._Louis_Museum (accessed 03/03/2016).

Melville, Herman. Moby-Dick. 1851. Ed. Harrison Hayford and Hershel Parker. New York: Norton, 1967.

Stadler, Ernst A. “Introduction.” Albert C. Koch. Journey through a Part of the United States of North America in the Years 1844-1846. Reprint. Transl. & Intro. Ernst A. Stadler. Carbondale and Edwardsville: Southern Illinois University Press, 1972. xxvii-xxxv.

van Riper, A. Bowdoin. Men Among the Mammoths. Victorian Science and the Discovery of Human Prehistory. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993.

FURTHER READING

Foster, Hoy, P.R.. “Dr. Koch’s Missourium.” The American Naturalist 5,3 (1871): 147-48.

Meltzer, David J. The Great Paleolithic War. How Science Forged an Understanding of America’s Ice Age Past. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015. https://books.google.de/books?id=adspCwAAQBAJ&pg=PA588&lpg=PA588&dq=J.D.+Dana+Koch's+Evidence&source=bl&ots=ziU-65bAKo&sig=t7132sbquQqpzpZrEdZ8k7sMbbo&hl=de&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjv_-TGiaXLAhXk63IKHYW4By4Q6AEIVTAJ#v=onepage&q=Melville&f=false

Owen, R. “Report on the Missourium now exhibiting at the Egyptian Hall, with an inquiry into the claims of the Tetracaudodon to generic distinction.” Proceedings of the Geologic Society of London 3,3 (1842): 82.

ILLUSTRATIONS

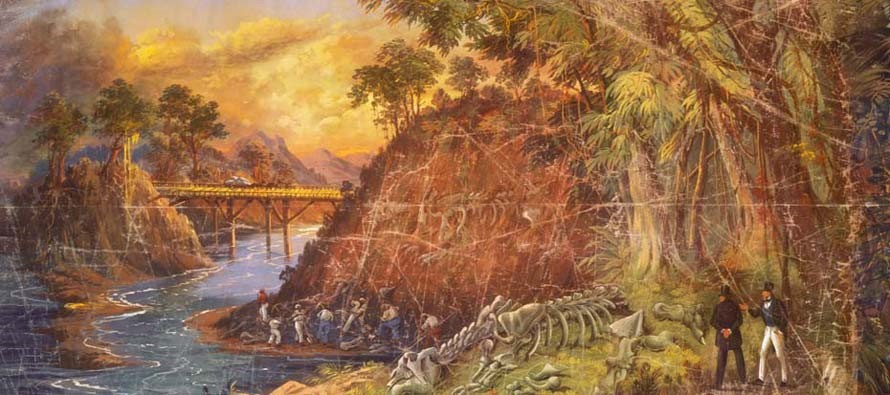

Figure 1: John J. Egan, Ice Age mastodon unearthed by Albert Koch in Kimmswick, Missouri in 1840. The two figures in the right are supposed to be Albert Koch (in white trousers) and Montroville Wilson Dickeson, the narrator and exhibitor of Egan’s panorama (McMillan). As Egan’s other images, this one emphasizes the contribution of the common laborers, most of them Black slaves. Monumental Grandeur of the Mississippi Valley, panorama, ca. 1850. Courtesy St. Louis Art Museum.

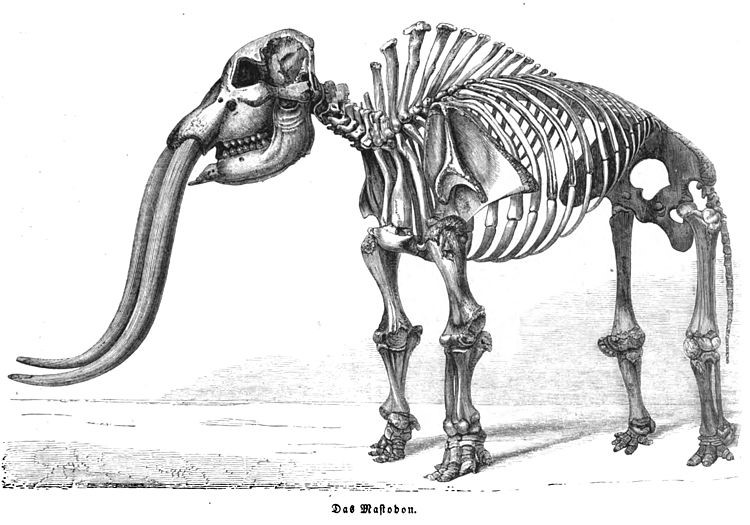

Figure 2: The Mastodon in Germany. From N.N., “Ein Riesenthier der Vorwelt.”Die Gartenlaube, Heft 29 (1856): 392–393.

Figure 3: A grossly exaggerated reproduction of the Missourium which accompanied Koch’s traveling exhibition. Koch rearranged his find and magnified its size bythe comparison with the Indian elephant. References to American Indians, whose legends Koch included in his show, can be found on the right hand sideand in the background (canoe). Source: http://extinctmonsters.net/tag/nhm-london/ (accessed 03/03/2016).

Figure 4: Koch’s “Missourium” remounted into a proper mastodon by experts in the Natural History Museum, London. Source: http://piclib.nhm.ac.uk/results.asp?image=069197&itemw=4&itemf=0001&itemstep=1&itemx=4