Mount Coffin

by Stefan Krause, 03/09/2016.

Summary

Mount Coffin was a once approximately 250-foot-high rock on the riverbank of the Columbia near the city of Longview, Washington State. It served as a burial site for the local indigenous population, the Cowlitz people. The rock was first described by Lieutenant William R. Broughton in 1792, who named it Coffin because of the dead bodies posited in canoes on the rock’s summit. Because of its striking features, Mount Coffin was an important landmark for indigenous people and early Western explorers such as Meriwether Lewis and William Clark. In the 20th century the former landmark was turned into a rock quarry, completely levelled in the 1950s, and has been used by the Weyerhaeuser Company as industrial area ever since. The slow destruction of Mount Coffin and the replacement of this geographical landmark by ‘colonial landmarks’ —such as factory buildings and logging bridges—illustrate the different ways of claiming, shaping, and stewarding land by indigenous and colonial agents.

When Royal Navy Lieutenant William R. Broughton—commander of the HMS Chatham and important member of the Vancouver expedition—began his journey on the Columbia River in October 1792, he was the second European explorer in these waters. The American Robert Gray sailed down the river only a few weeks earlier and named it after his vessel: the Columbia.[1] Broughton, however, drew a very detailed map of the river, recording and naming several geographical features along the Columbia River. One of these features “was a remarkable mount, about which were placed several canoes, containing dead bodies,”[2] which he named ‘Mount Coffin.’ The rock is located near the confluence of the Columbia and the Cowlitz River (in the area of today’s Longview) and is not to be confused with ‘Coffin Rock’—another indigenous burial site on an isolated rock up the river.

Burial Site and Geographical Landmark

In the following years several explorers mentioned the strange rock in their journals. In November 1805, the famous explorers Meriwether Lewis and William Clark passed by this landmark and described it as “a verry [sic] remarkable Knob.”[3] In 1811, David Stuart of the expedition of the German-American merchant John Jacob Astor noticed Mount Coffin when he was journeying up the Columbia in order to set up a fur trade outpost. Stuart remarks that “[a]t one part of the river, they passed, on the northern side, an isolated rock, about one hundred and fifty feet high, rising from a low marshy soil, and totally disconnected with the adjacent mountains. This was held in great reverence by the neighboring Indians, being one of their principal places of sepulture.”[4] A few years later, in 1841, Lieutenant Charles Wilkes of the U.S. Exploring Expedition climbed to the summit of the rock to make astronomical observations, in the course of which he accidentally set parts of the indigenous burial site on fire.[5] Another version of this incident was given by the Cowlitz leader Roy I. Rochon Wilson, who assumed that “Wilkes had planned the fire as a means of improving the ecology of the site, but it became another oppressive action of the incoming tide of the new dominant society.”[6] The early descriptions by Western explorers hence leave the impression that Mount Coffin’s status as a landmark and sacred site for the indigenous locals was often understood and accepted, although episodes like Wilkes’ visit show that the arrival of the white man began to leave destructive traces.

The Sad Fate of Mount Coffin

The impact of colonialism and Westward Expansion became undeniable after the establishment of a land claim program in the Oregon territory in the 1850s and the purchase of the land surrounding Mount Coffin by D.W. Bush.[7] Bush held on to the land for more than four decades before he sold it to the Star Sand and Gravel Company from Portland in 1908. By this time, the remarkable rock had become a popular spot for visitors, lovers, and grave robbers, who removed arrowheads and other objects from the Native American burial site. Subsequently, the rock served as a stone quarry used to provide material for jetties and roads, before the Weyerhaeuser Company—established by the German-American entrepreneur Friedrich Weyerhäuser—from Longview purchased the area around Mount Coffin in the 1920s. The local industry continued to quarry the rock until—in 1941—the landmark was reduced to half of its former size[8] and completely leveled by the 1950s.

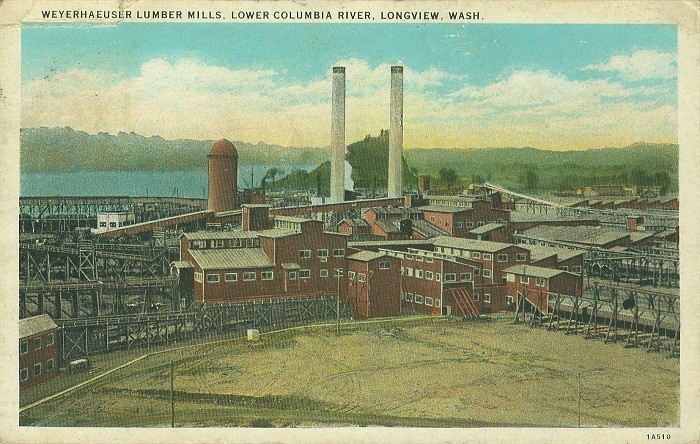

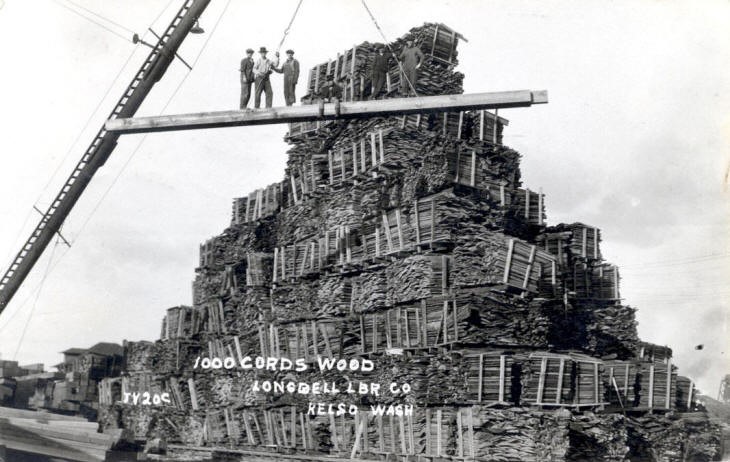

This change is illustrated in pictures and postcards. Photographs taken in the 1920s show Mount Coffin as a landmark towering over the surrounding industry and harbor of Longview. However, these pictures also depict how the rock was slowly being deprived of its basalt sediment and its status as ceremonial site. Postcards from the 1930s show how the geographical landmark has been surpassed by the buildings of the Weyerhaeuser Company, providing an alternate or colonial landmark for the region (figure 1). Generally, landmarks are prominent objects or geographical features shaping the face of a certain landscape, often serving as a guide for travelers. Yet whereas Mount Coffin was an example for a natural landmark (although slightly modified by native burial practices), the buildings of the local industry have to be considered as exclusively man-made landmarks. Moreover, these industrial facilities are among the first permanent and prominent structures erected by European-Americans in the area. It is this process of claiming and transforming indigenous land through conspicuous structures built by Western agents that makes landmarks like the lumber mills of Longview ‘colonial.’ Eventually, Mount Coffin was replaced by ‘colonial landmarks.’ Constructions and buildings of the local lumber industry emphasized how the character of the region has changed due to its geographical and manmade features. Examples for these new landmarks are—next to facilities of the Weyerhaeuser lumber mills—Baird Creek logging bridge (figure 2) and the piles of wood produced by the lumber mills (figure 3), which sometimes ironically even seemed to resemble Mount Coffin.

The Peculiar Logic of ‘Progress’

The destruction of Mount Coffin and the shift in the local landmarks can be considered as a gradual process, which has sometimes been interpreted within the peculiar logic of ‘progress.’ For example, a poem by Mrs. Charles H. Olson—a citizen of Longview’s neighboring city Kelso—presented in the local news in 1935 reads:

“That Mt. Coffin, majestic tree crowned rock

Beloved by the Indians, a consecrated spot,

In all her beauty and grandeur renowned,

The coming of ‘progress’ was tearing her down.”[9]

For the most part, this ‘progress’ took place without involving the local indigenous population. Only in 2000, the Cowlitz people achieved federal recognition as a tribe. Eventually—in 2005—members of the tribe visited the location of Mount Coffin to sanctify the site.[10] During this ceremony they cleansed the site in order to honor their ancestors and to come to terms with the past. This past has been shaped by different agents who cannot always be identified. Yet it is important to underline that ‘progress’ cannot be considered an agent and that the transformation of landscapes and landmarks is quite often an active process controlled by specific groups of people. Similarly, the story of Mount Coffin has been written by different people and it is a story that illustrates how indigenous and colonial agents have shaped the past and the present of the Pacific Northwest.

NOTES

[1] Hayes, Derek. Historical Atlas of the Pacific Northwest: Maps of exploration and discovery: British Columbia, Washington, Oregon, Alaska, Yukon. Seattle: Sasquatch Books, 1999. 85.

[2] Vancouver, John. A Voyage of Discovery to the North Pacific Ocean, and Round the World; in Which the Coast of North-West America Has Been Carefully Examined and Accurately Surveyed. Undertaken by His Majesty's Command, Principally with a View to Ascertain the Existence of Any Navigable Communication between the North Pacific and North Atlantic Oceans; and Performed in the Years 1790, 1791, 1792, 1793, 1794 and 1795, in the Discovery Sloop of War, and Armed Tender Chatham, under the Command of George Vancouver. Vol. III. London: Printed for John Stockdale, 1801. 98.

[3] Lewis, Meriwether, Clark, William, et al. November 6, 1805. The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. Ed. Gary Moulton. Lincoln: U of Nebraska Press, 2002. The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. 2005. U of Nebraska Press / U of Nebraska-Lincoln Libraries-Electronic Text Center. 10/05/2005.

[4] Irving, Washington. Astoria; or Anecdotes of an Enterprise Beyond the Rocky Mountains. Edgeley W. Todd, ed. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1964. 99.

[5] Wilma, David. “Cowlitz County -- Thumbnail History.” HistoryLink.org.www.historylink.org/index.cfm (access date 12/15/2015).

[6] Wilson, Roy I. Rochon. “Roy I. Rochon Wilson Commentary: The Tragic Destruction of Coffin Rock.”

[7] Wilson, Roy I. Rochon. “Roy I. Rochon Wilson Commentary: The Tragic Destruction of Coffin Rock.”

[8] Topinka, Lyn. "Mount Coffin, Washington." ColumbiaRiverImages.com.columbiariverimages.com/Regions/Places/mount_coffin.html (access date 12/15/2015).

[9] Johnson, Brooks. “History month: Grave robbers.” The Daily News Online. tdn.com/news/local/history-month-grave-robbers/article_64cc51b6-0199-5891-89d9-d1623beb1593.html (access date 12/15/2015).

[10] Ousley, Sally. “Cowlitz sanctify Coffin Rock.” The Daily News Online. tdn.com/business/local/cowlitz-sanctify-coffin-rock/article_b940b538-7592-51ce-9dc5-b657fcf645ba.html (access date 12/15/2015).

ILLUSTRATIONS

Figure 1 (ca. 1930): Topinka, Lyn. ColumbiaRiverImages.com. www.columbiariverimages.com/PennyPostcards/Images/PC_weyerhaeuser_mill_with_mount_coffin_ca1930.jpg (access date 12/15/2015).

Figure 2 (1940): LPL Longview Room Photographs. Longview Public Library. contentdm.longviewlibrary.org/cdm/singleitem/collection/lvr/id/926/rec/24 (access date 12/15/2015).

Figure 3 (1920s): Walker, Craig. R. A. Long Historical Society. www.ralonghistoricalsociety.org/1000crd.htm (access date 12/15/2015).

Figure short version (1928): LPL Longview Room Photographs. Longview Public Library. contentdm.longviewlibrary.org/cdm/singleitem/collection/lvr/id/2740/rec/4 (access date 12/15/2015).