Naming Mountains: Denali vs Mount McKinley

by Alexander Bräuer, 11/07/2015.

Summary

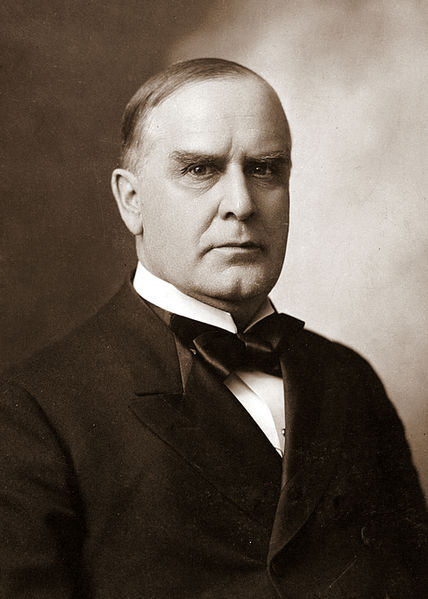

On August, 30th 2015 the Obama administration approved the change of name of the highest mountain in Alaska from Mount McKinley to Denali after a decade-long hold-off by Ohio representatives in the United States Board on Geographic Names. Denali had been named Mount McKinley by a gold prospector in 1896 after the presidential-candidate William McKinley, ignoring the indigenous name Denali that remained popular in the local area until today. As the decade-long struggle on the highest political level shows, naming is a process with deep political, social and cultural consequences. In the end, the dispute was decided in favor of a renaming by a powerful coalition of indigenous groups and state politicians. Politicians on the national level were no longer able to combat the process of decolonizing the highest mountain in Alaska.

On August, 30th 2015 the Obama administration approved the change of name of the highest mountain in Alaska from Mount McKinley to Denali after a decade-long hold-off by Ohio representatives in the United States Board on Geographic Names. Denali had been renamed Mount McKinley by a gold prospector in 1896 after the then presidential-candidate (and later president) William McKinley, ignoring the indigenous name Denali that remained popular in the local area until today. As the decade-long struggle on the highest political level shows, naming is a process with deep political, social and cultural consequences. Therefore, this article addresses some of the reasons behind the dispute and explains why the naming of mountains plays an important role for the history of colonialism.

Mountains always presented challenging natural conditions.

Ascent and altitude differences created difficult climate conditions and unfavourable soils for agricultural production. Since early times local populations successfully developed sophisticated practices to live under these conditions. These cultures mostly followed a yearly migration rhythm taking the changing natural conditions on the different altitudes into account. On the other hand, they cultivated economic practices like terrace cultivations to deal with steep ascents and to use it for their advantage. Because they were so closely observed as seismography of geological and ecological events, mountains played an important role in the cultural imagination and mythologies of indigenous people.[1]

Modernity and Colonialism

Today, the presentation of mountains is influenced mostly by two interrelated processes: modernity and colonialism. Both were primarily driven by the increase of agricultural production centred in the lowlands of Europe, providing opportunities for social, economic and cultural changes and a territorial expansion of political power. At the same time, these processes led to a new interpretation of the relationship between lowland and mountains. Even before seen as obstacles for travelers and natural borders for political governance, mountains now also became the antidote of modernity and spaces to conquer and settle. Because of this development the habitants of the mountain regions were constructed as subjects to be reformed or even erased.[2] Indigenous people living in the mountain regions were thought to be at a double disadvantage because they were considered to be both of inferior race and not able to address the new modern potential of the mountains.[3]

Practices and Techniques

Together with the new discourses on mountains came new practices and techniques. Mountains as part of the wilderness had to be protected – with the help of national parks (link to national parks – even against the interests of their own inhabitants. Mountaineering, as a practice, grew and white men challenged their bodies in order to demonstrate their own supremacy over nature. Interactions with the inhabitants were not desirable but nevertheless necessary to hire them as local guides during the sophisticated climbing operations. Although they remained generally invisible in the reports, indigenous people provided the necessary labor and knowledge about the natural conditions.

(Re)naming Mountains

One of the most important practices in connection to the modernization and colonization (of mountain regions) was a (re)naming of its geographical features. Geographical naming constituted a powerful instrument of colonialism, which revolved around the appropriation of indigenous land. It helped to dispossess indigenous people, whose names for the same places were erased, and created imaginative ownership of the new lands. Because settlers wanted to “feel at home” they renamed the landscapes after their own leaders and places of their old homelands. In short, naming constituted a powerful practice to come to terms with an otherwise unjust and violent conquest of foreign lands. Mountains as important navigation points and widely seen landscape features were in special need to be renamed, usually by the first explorers “discovering” them.

Indigenous Resistance

Local and indigenous people looked at these developments with curiosity and (re)acted with diverse measures. Indeed, often they were able to ignore the renaming of their lands because indigenous names remained in use during economic and political interactions on the ground. Therefore, sometimes several indigenous names coexisted with the names on the official map and created, until today, starting points for indigenous resistance to colonialism. Denali represents one of these starting points for indigenous resistance and the renaming becomes a substantial moment of decolonization and indigenous empowerment.

Renaming Denali

Since 1975, political debates on Denali were not running along the traditional party-lines between democrats and republicans, rather they were informed by local and state partisanship. Alaskan politicians and activists lobbied for a renaming and already changed the name on the state level in 1975, whereas delegates from Ohio, home state of William McKinley, worked against the renaming on the national level. This dispute shows that Native Americans in Alaska were successful in linking their campaigns to state interests and were ultimately able to present the renaming as a matter of state patriotism, an Alaskan project supported by the whole local population. Strategies of cooperation with environmental or local grassroots movements seem to become more and more popular because references to colonial implications of naming are often not enough for a successful campaign.

Mountain areas represent an interesting case study for decolonization because they were relatively recently affected by the processes of colonisation. Therefore, traces of indigenous culture and resistance are still very prominently on the ground. The naming dispute on Denali was situated at the nexus between colonial and decolonial discursive camps, but also in between the local and state level. The dispute could be solved in favor of an indigenous renaming of the mountain because indigenous groups were able to form a powerful coalition with local and state politicians. Moreover, the naming dispute serves as a symbolic battlefield for ideas of American Antiquity influenced by discourses of colonialism and landownership. Naming geographical features represents a powerful way of controlling narratives of the past. However, what remains crucial for naming disputes are the practices on the ground – as the continuous naming of the mountain in the local area as Denali. The very presence and use of indigenous names represents not only a challenge to narratives of colonialism but gives evidence to the existence of vivid indigenous cultures still living with, from and on their land.

NOTES

[1] See Julie Cruikshank, Do Glaciers Listen? Local Knowledge, Colonial Encounters, and Social Imagination. Vancouver: British Columbia University Press, 2005.

[2] For the history of mountains in the modern age see for example: Mathieu, Jon. Die dritte Dimension: Eine vergleichende Geschichte der Berge in der Neuzeit. Basel: Schwabe Verlag, 2011.

[3] This history is informed by Western ideas and a focus on the Alps. However, prominent exceptions exist especially in areas with tropical climate such as the Andes of South America. Here, mountains and altitude led to the emergence of high cultures and yielded agricultural advantages.

ILLUSTRATIONS:

Figure 1: View of Denali; Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Denali; accessed: 10/24/2015.

Figure 2: Location of Denali; Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Denali; accessed: 03/30/2016.

Figure 3: William McKinley; Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_McKinley; accessed: 03/28/2016.