A T. Rex named Sue

by Alexander Bräuer, 03/11/2016.

Summary

Sue holds a rather dubious world record: 85%. She is currently first place on the list of the most complete specimina of Tyrannosaurus rex with 85 per cent of the bones preserved and found. Named after her discoverer, Susan Hendrickson, she is currently preserved in the Field Museum in Chicago. But Sue is more than a collection of bones. 67 million years ago, she was once a living animal. After her death, she became conserved in mud and stayed there until 1990, when she was unearthed, named, fought over in court, examined, sold and displayed in various ways. The adventurous story of her bones represents a window into our construction of the distant, pre-human past of America over the last 25 years. This article will follow Sue’s bones and show that she can help us unmask some important trends for the construction of American antiquity.

The Living Sue

Sue’s life in pre-human times for the most part remains a mystery. In fact, we don’t even know if Sue is a she. He or she probably weighed more than 6,4 tons and stood at more than 4 meters high and 13 meters long when alive. The bones indicate an age of 28 years when s/he died, making Sue the T-Rex with the greatest longevity known. During her life, she suffered from multiple injuries, although none of them proved to be deadly. Indeed, her cause of death is unknown, although she probably died accidentally in a river bed, thereby getting covered by mud and quickly becoming one of the best preserved specimens of Tyrannosaurus rex.

The Unearthing of Sue

In 1990, members of the Black Hills Institute, a private corporation specializing in the excavation of fossils, visited the Cheyenne River Indian Reservation in western South Dakota, and unearthed an Edmontosaurus. On their way back, a flat tire led a straying group member to the discovery of a Tyrannosaurus rex. The specimen was named after its discoverer Susan “Sue” Hendrickson, an already established explorer with an already colorful résumé as a diver, amber miner and paleontologist. Thus, the fossil moved – through the naming – on from a collection of bones to an individual exemplar with unique characteristics.

The Battle over Sue

The battle of the bones began after the find became known to the scientific community and the public. The Black Hills Institute had paid the landowner, a Sioux named Maurice Williams, 5,000 US dollars for the fossil. However, after the significance of the find had become public, a legal battle over the bones between the landowner, the Black Hills Institute and the Federal government unfolded. In the end, a judge decided that the land on which the fossil was found belonged technically to the government who held it in trust for the local Sioux tribes on the basis of the 1887 Allotment (Dawes) Act. Even before, the FBI and National Guard had raided the Black Hills Institute and seized the fossil in a spectacular operation. The dispute over the ownership of the fossil derived from multiple factors including unclear land ownership, indigenous claims and the fact that bones were excavated in different properties (article on the legal battle over Sue). Another side of the dispute was concerned with the perception of a battle between private adventurers trying to make money with fossils and public institutions and researchers, who represent science and the public good. The 1980s and 1990s constituted a climax for the fossil trade.[1] The media highlighted concerns of fossils ending up in the collections of private persons and published stories of private excavations ending with significant damage to the fossils because of technical errors. However, a closer look at the agents involved in these conflicts reveal that many concerns were exaggerated. Most public institutions depended more and more on wealthy private supporters and private corporations such as the Black Hills Institute usually worked closely together with universities or museums. Therefore, many agents had a hybrid background, closely related to private and public entities. Indeed, the excavation of Sue by the Black Hills Institute is today seen as an exemplary operation, including modern techniques like extensive video recording of the dig.

The Auctioning of Sue

In the end of the legal battle stood an agreement between the government and the indigenous land owner Maurice Williams to sell the fossil on a public auction. The money gained by the Sotheby’s auction in 1997 went to Maurice Williams. As mentioned before, the 1990s were a good time to sell fossils on the market and Sue as the biggest, oldest and most complete Tyrannosaurus rex represented by far the greatest price ever offered for a fossil. A coalition by private corporations and public institutions – compromising among others the Field Museum in Chicago, the California State University System, McDonalds and Walt Disney Parks and Resort – purchased Sue for 7,6 million dollars (plus buyer’s premium 8.36 million dollars) making her a valuable commodity. The Field Museum wanted to examine and display the fossil in their public collection and the other public donors supported this effort. On the other hand, it is no accident that companies such as McDonalds, and especially Walt Disney, had a keen interest in Sue. At least since Stephen Spielberg’s movie Jurassic Park (1993), the Tyrannosaurus rex was well known to the American audience and Disney pursued their own film projects about dinosaurs [Dinosaur (2000)]. Disney’s and to a certain extent McDonald’s business model centered around extinct species imagination and the 1990s experienced a new public interest in movies and other cultural products about animals [Lion King (1994)], nature [Tarzan (1999)] and history [Aladdin (1992), Pocahontas (1995), Hook (1991)]. New computer technologies allowed for a much more entertaining and cheaper display of (extinct) animals and helped to realized ambitious projects. Children presented the main target group of this wave.

The Display of Sue

Since imagination couldn’t be put in the bank, Disney and McDonalds expected a more direct return from the purchase of the fossil. After the auction, several replicas of Sue were produced which not only complemented the original bones in the Field Museum in Chicago, but supplied a traveling exhibition presented by McDonalds to “bring the story of Sue - … - to families and children.”[2] Furthermore, replicas for the Animal Kingdom Theme Park in Disneyland were fabricated.

In between gift and food shops, a picnic area, a designated smoking area, not far away from the “Boneyard: Fossil Fun Site,” where kids can dig for their own dinosaurs and experience the adventure of unearthing Americas distant past, a replica of Sue was presented for children and tourists. Furthermore, one of two labs for the preparation of the original bones was built in Disneyland – the other one was situated in the Field Museum which organized the scientists for both labs. By their placement in Disneyland, the bones were incorporated into a multitude of colonial discourses (“meeting of Pocahontas at Discovery Landing”; “Kilimanjaro Safaris”, “Wild Africa Trek”; exploring the animals of Asia and Africa; conquering nature in the “Everest experience”) and helped to create a truly American (historical) experience.

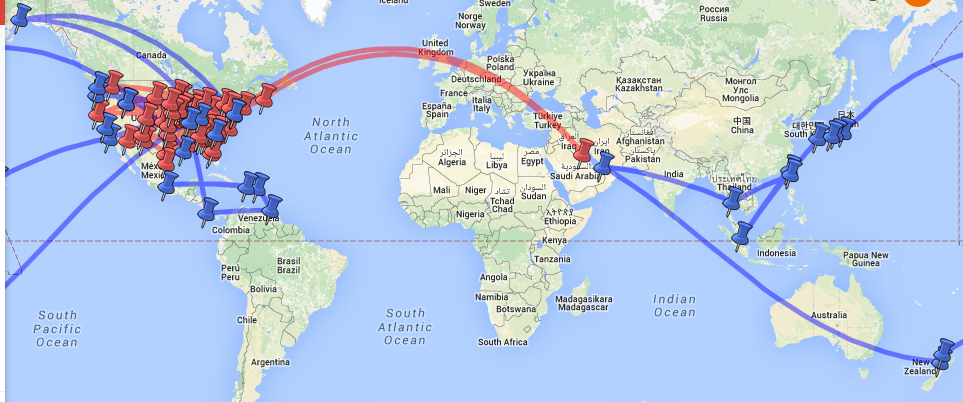

Overall, Sue’s bones multiplied and went global at the same time. After a first tour concentrating on stations on the North American continent, the traveling exhibition went for a second tour including venues in New Zealand, South America and Asia.

The investments in the bones were just too big to justify a limited display without creating several global business models. Even in the Field Museum, the bones were separated and distributed, as the most prominent part, the skull, received a special place on a gallery. Thus, the bones of Sue show us how (the stories about) artifacts of an American antiquity can inspire human imagination and thereby can themselves become powerful and economic valuable objects.

NOTES

[1] Kjærgaard, Peter C. “The Fossil Trade: Paying a Price for Human Origins”. Isis 103:2 (2012), p. 340-355, p. 346.

[2] https://www.qsrmagazine.com/news/mcdonalds-dinosaur-exhibit-tours; accessed 03/11/2016.

ILLUSTRATIONS

Figure 1: Tyrannosaurus rex, named Sue, in the Field Museum, Chicago. The original skull is displayed separately in the museum. Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sue_%28dinosaur%29#/media/File:Sues_skeleton.jpg; accessed 03/11/2016.

Figure 2: Skull of Sue displayed separately in the Field Museum, Chicago. Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Sue_skull.jpg; accessed 03/23/2017.

Figure 3: Dinoland in Disneyland displays one Replica of Sue. One lab for the preparation of the bones was also situated in Disneyland. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Sue_%28dinosaur%29#/media/File:Replica_T._rex_skeleton,_DinoLand_USA_2.JPG; accessed 03/30/2016.

Figure 4: Map of the traveling exhibition “A T. Rex Named Sue”. Shown are the exhibition venues of the 1st tour in red (2000-2012) and 2nd tour in blue (2012-ongoing). Source: https://www.google.com/maps/d/viewer?msa=0&mid=zv6dND5TH9qI.kJTvY9i0NULk; accessed 03/11/2016.