Introducing the 'Tiere der Urwelt' Trilogy: Trading Cards as Artifacts

by Alexander Bräuer, 04/08/2016.

Summary

Trading cards were omnipresent in the popular culture of Germany before the First World War. Stollwerck, the leading producer of trading cards, alone distributed 200 million cards between 1896 and 1899. Trading cards usually combine visual representations on the front with textual content on the back and some sort of advertisement by the producer – mostly companies associated with colonial products. The trading card series Tiere der Urwelt ("animals of the primeval world") was produced by the Theodore Reichardt cacao company, painted by Heinrich Harder, and written by Wilhelm Bölsche. A selection of 30 ‘prehistoric’ animals were presented in their natural surroundings and explained in short texts. As such the series influenced not only the construction of an (American) antiquity in Germany at the beginning of the 20th century, but remained – until today – important for the depiction of ‘prehistoric’ times. The "Introduction" will provide some background information on the series and introduce a trilogy of three articles on Tiere der Urwelt, dealing with different aspects of this unique artefact.

The late 19th and early 20th century witnessed the Golden Age of postcards and related formats like trading cards. The medium reached broad masses, and German cards were spread all over the world. Printers from Germany dominated the world market and produced cards in a variety of languages which were then shipped to other countries like the USA or France. Starting in the 1860s, Stollwerck, a chocolate manufacturer from Cologne, had produced probably the most famous trading cards in Germany, known for their quality imagery and informative texts. Since then, trading cards and colonial products worked hand in hand and popularized the colonial project in the German public. Providing information about the colonies on trading cards which accompanied colonial products such as coffee, tea, sugar, chocolate or tobacco proved to be a profitable business. Thereby, consumers could value the consumption of such ‘exotic’ and uncommon products even more.

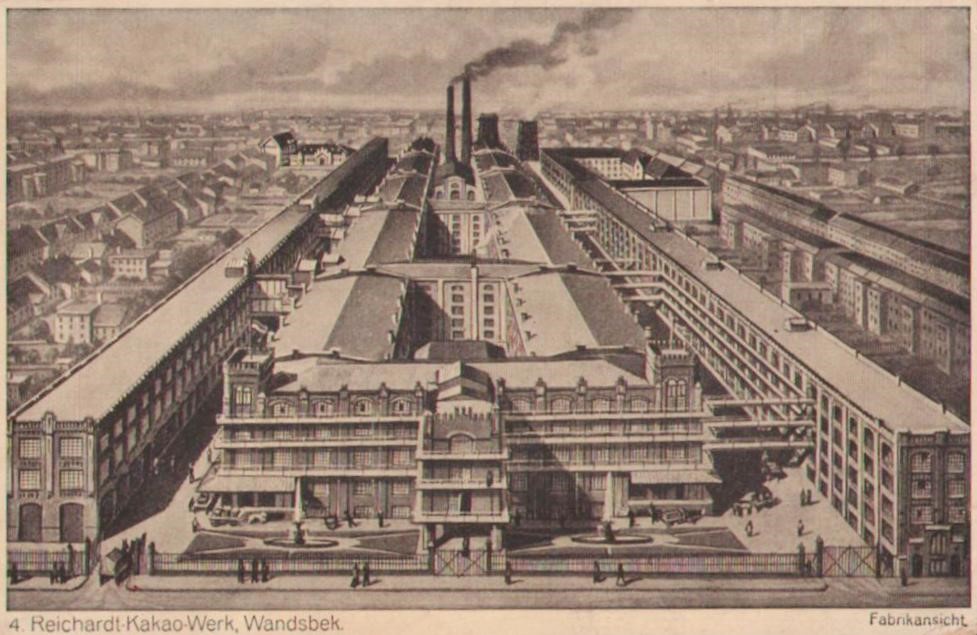

The collector’s trading cards Tiere der Urwelt (“Animals of the prehistoric world”) were published by the Theodore Reichardt cacao company, one of the biggest producers of chocolate in the world, in Wandsbek, Hamburg. They circulated widely and were probably given away by the Theodore Reichardt company as a supplement to their cacao boxes, for free as advertisements, or sold separately.

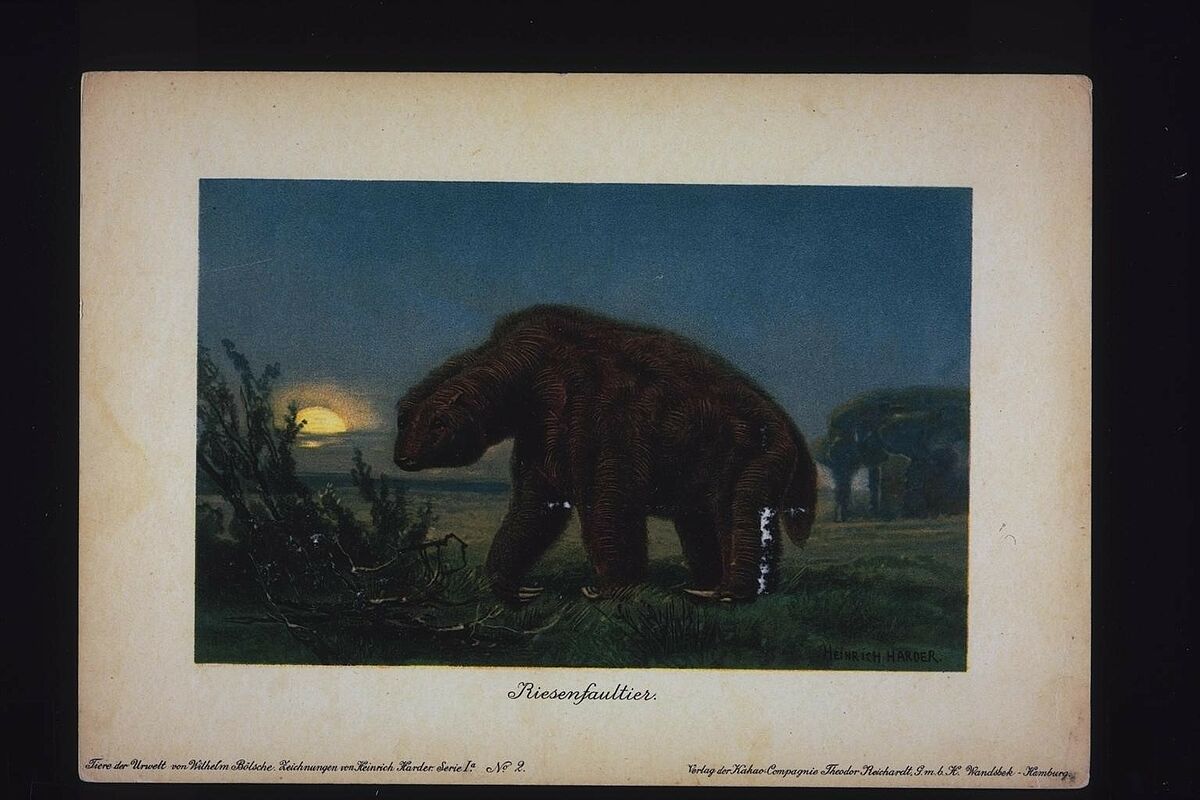

Children may have been one target group, but the high quality pictures and especially the elaborated texts also hint at a much broader consumption by adults. Tiere der Urwelt consisted of three series of cards (Ia, II and III), each one containing 30 cards. Series Ia and III were illustrated by Heinrich Harder, series II by F. John, and all three were inscribed by Wilhelm Bölsche. The Trilogy will concentrate on series Ia, published ca. between 1902-1916 and consisting of 30 colored illustrations in 19,6 x 27,4 cm. Each card had a chromo-lithographic picture of an animal on the front and a text with further information on the back. All cards of the series could be combined in a collector’s album produced by the company. Here, the trading cards will be treated as an artifact, because through their various consumptions Tiere der Urwelt became influential for the construction of an American antiquity in Germany.

The Creators: Heinrich Harder and Wilhelm Bölsche

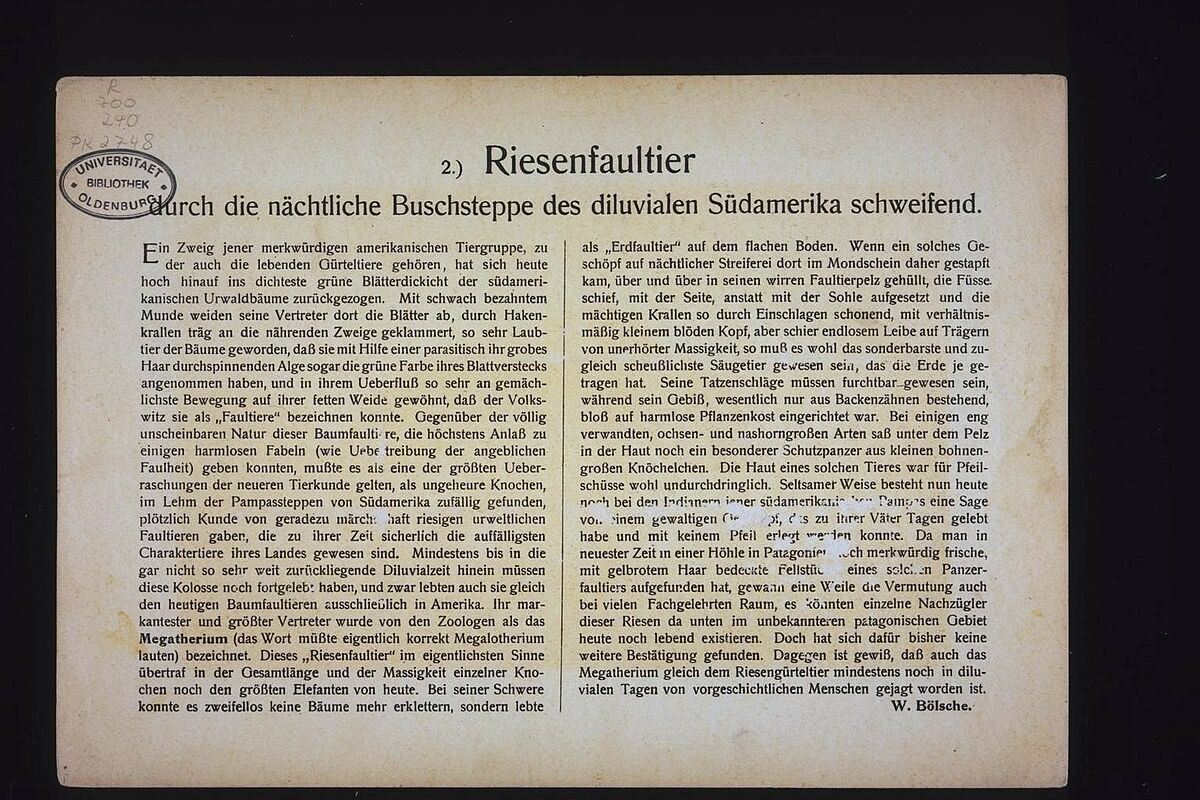

Heinrich Harder, a painter born in Putzar, Vorpommern, created the illustrations for the recto of the trading cards. Harder started his career with landscape paintings before he developed into one of the most accomplished painters for ‘prehistoric’ animals. He could rely on the work of other well-known illustrators like Charles R. Knight who became famous by imagining and painting animals from the distant past. His paintings usually show the animals in their natural environment and are remarkable for their high quality. Harder teamed up with the writer Wilhelm Bölsche for the trading cards and several other projects like newspaper articles. In his very productive life he became famous for making scientific theories and ideas accessible for a broader audience. As such he was very influential in the establishment of community colleges (Volkshochschulen) in Germany and one of the first writers of popular non-fiction books (Sachbuch). The texts for the trading cards by Bölsche went much further than a pure description of the animals on the recto. He elaborated on their position in the evolution, the location of their habitat, selected places of famous findings, their probable nutrition and behavior, fables and mysteries from indigenous people, and scientific disputes about the animals. In the analysis of the trading cards, both Heinrich Harder’s illustrations and Wilhelm Bölsche’s texts came together and developed an interplay that made trading cards such a fascinating medium for communicating certain ideas of American antiquity to the common people.

Tiere der Urwelt since the early 20th century

Heinrich Harder’s paintings created a ‘prehistoric’ landscape resembling many ideas about colonial landscapes in the early 20th century. As outlined in an article on the contemporary significance of Tiere der Urwelt,the paintings of Heinrich Harder – together with the descriptions by Wilhelm Bölsche – should be understood as a promotion of their interpretation of Darwin’s theory of evolutionary in order to justify settler colonialism and the genocide on the indigenous population. However, the trading cards and especially Harder’s illustrations had a function even after the idea of the vanishing Native American race had become obsolete. The trading cards themselves became less important as their circulation ceased and only limited exemplars were traded by a small group of collectors and enthusiasts. However, in the late 1960s the illustrations of Heinrich Harder were separated from the text of Wilhelm Bölsche and loaded with new meanings promoting the “Pleistocene Overkill” hypotheses, a hypothesis that blames human, i.e. indigenous people, for the extinction of the Pleistocene megafauna.

An “American” Antiquity in Tiere der Urwelt?

Bölsche’s interpretation of Darwinism cannot and should not be located in one or two specific areas of the world. Bölsche rather aims for a model that could explain all animals around the whole world no matter in what time frame they are or were living. Consequently, some trading cards even do not mention a possible habitat, leaving it to the consumer to assign the animal to a specific area. Not surprisingly the location of animals is much more specific when dealing with land-locked animals in contrast to creatures of the air or of the oceans. Harder’s paintings deliver another aspect of the location by depicting the animals in their – often exotic – natural environments.

At least 12 animals out of 30 have a connection to America via habitat or archaeological findings. Myths by indigenous people or the local population are featured prominently in some trading cards, but only in order to explain their own origins and never as independent scientific sources for the location of animals. However, the numerous references to America do not necessarily constitute a breakaway from the general concept since other colonized areas such as Australia, New Zealand, South east Asia, Africa, and northern and eastern Russia are mentioned repeatedly as well. Furthermore, important archaeological findings in Germany are again and again linked to the ‘prehistoric’ animals. When looking at the location of the animals, it becomes obvious that the trading cards are reenacting the colonial center-periphery relationship in their construction of a distant past. The animals at the core (Europe and particular Germany) have usually been extinct for a long time, whereas in the ‘uncivilized’ periphery (America, Africa, Oceania, and Asia) the ‘prehistoric’ animals are often still alive or, in the case of the settler colonies, only at the verge of extinction. This fits well into contemporary conceptions of modernity that constructed indigenous societies (or natural colonial environments) as ancient and as being stuck in certain ‘prehistorical’ periods, in contrast to modern, dynamic Western societies.

The value of the trading cards for the construction of an “American” antiquity, therefore, resides in the fact that the American distant past is integrated into an ‘evolutionist’ history of the whole world (ignoring. This dynamic obviously changed when the paintings by Harder became detached from the cards and went global at the end of the 20th century. The following three articles will provide some insights into the fascinating and different interpretations of artifacts such as trading cards for the construction of an American antiquity through time and space.

Read more about Tiere der Urwelt in the Trilogy:

Part 1 - Tiere der Urwelt: Darwinism and Colonialism

Part 2 - Tiere der Urwelt: Creating a ‘Prehistoric’ Landscape

Part 3 - Tiere der Urwelt: Harder’s Illustrations, Wikipedia & the “Pleistocene Overkill”

FURTHER READING

Cain, Victoria E. M. “’The Direct Medium of the Vision’: Visual Education, Virtual Witnessing and the Prehistoric Past at the American Museum of Natural History, 1890-1923.” Journal of Visual Culture 9.3 (2010), p. 284-303.

Moser, Stephanie & Clive Gamble. “Revolutionary Images: The Iconic Vocabulary for Representing Human Antiquity.“ In: Molyneaux, Brian L. (ed.). The Cultural Life of Images: Visual Representation in Archaeology. London & New York: Routledge, 1997, p. 184-212.

Sarasin, Philipp. “”Zäsuren biologischen Typs”: der Kampf ums Überleben bei Wilhelm Bölsche, H. G. Wells und Steven Spielberg“. In: Schramm, Helmar & Schwarte, Ludger & Lazardzig, Jan (eds.). Spuren der Avantgarde: Theatrum anatomicum: frühe Neuzeit und Modern im Kulturvergleich. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 2011, pp. 443-459.

Zeller, Joachim. Bilderschule der Herrenmenschen: Koloniale Reklamesammelbilder. Berlin: Links, 2008.

Zeller, Joachim. “Harmless “Kolonialbiedermeier”? Colonial and Exotic Trading Cards.” In: Langbehn, Volker (ed.). German Colonialism, Visual Culture, and Modern Memory. New York: Routledge, 2010, p. 71-86.

ILLUSTRATIONS

Figure 1: Theodor Reichardt Kakao Compagnie, Hamburg: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Reichardt-Kakao-Werk.jpg; accessed 03/27/2016.

Figure 2: Front (recto) of Trading Card No. 2 of Tiere der Urwelt. Source: Tiere der Urwelt: Rekonstruktionen nach verschiedenen wissenschaftlichen Vorlagen. Wandsbek-Hamburg: Verl. der Kakao Compagnie Theodor Reichhardt, ca. 1900. diglib.bis.uni-oldenburg.de/retrodig/buch.php; accessed 03/27/2016.

Figure 3: Back (verso) of Trading Card No. 2 of Tiere der Urwelt. Source: Tiere der Urwelt: Rekonstruktionen nach verschiedenen wissenschaftlichen Vorlagen. Wandsbek-Hamburg: Verl. der Kakao Compagnie Theodor Reichhardt, ca. 1900. diglib.bis.uni-oldenburg.de/retrodig/buch.php; accessed 03/27/2016.